Top Ten: Nasty Women in Literature

/By Tricia Woodcome

From #TrumpBookReports to #TrumpANovel and now to #NastyWomenRead, the Republican Presidential candidate has inspired a literary resurgence in the Twittersphere. Within minutes of Donald Trump referring to Hillary Clinton as "such a nasty woman" during last week's third Presidential debate, self-proclaimed nasty women proudly embraced the mantle. The nasty woman trope is by no means a new phenomenon, and literary classics can prove it. Typified by independent minds, perseverance, unshakeable self-control, occasional arrogance, and unlimited imagination, these literary heroines have shown time and again that nastiness is not only an indispensable weapon -- it's an attitude all women should proudly adopt.

Here are ten of literature's most infamous nasty women.

1. Lady Macbeth, Macbeth, William Shakespeare

Behind every nasty man, there's an even nastier woman. This could not be truer than in the case of Shakespeare's most notorious female antagonist, who manipulates her husband into murdering his way to power. Permanently stained by the bloodshed she provoked, Lady Macbeth is driven to an insomniac madness of which one can't help but be in awe.

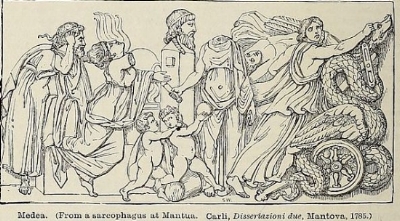

MEDEA (Source: WIKIPEDIA)

2. Medea, Medea, Euripides

The granddaughter of the sun god Helios and wife to hero Jason, Medea is not to be underestimated. Armed with rage after her beloved Jason's betrayal, Medea kills their two children. Feared by men and women alike, Medea's infanticide represents not only a cruel act of revenge, but also a bloody, tragic and nasty liberation.

3. Lisbeth Salander, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Stieg Larsson

Stieg Larsson's anti-heroine has an impressive (if frightening) capacity for violence and a hostility aptly feared by men. A rape survivor, Lisbeth takes pride in avenging her attacker in a haunting, nasty scene involving a taser, an anal plug and a bloody tattoo.

HESTER PRYNNE (Source: WIKIPEDIA)

4. Hester Prynne, The Scarlet Letter, Nathanial Hawthorne

Branded by her adulterous sin with a bright red "A," Hester endures her neighbor's contemptuous glares and becomes one of the most prominent flawed heroines in the literary canon. As Evan Carlton, literature professor at the University of Texas, Austin, explained, Hester's story "is really the drama of the patriarchal society's need to control female sexuality in the most basic way."

5. Emma Bovary, Madame Bovary, Gustave Flaubert

Deceptive, adulterous and frivolous, Emma's plight is the symptom of the limits placed on women in the misogynistic context of the nineteenth century. Instilled with her novels' romanticism, Emma fights as nastily as she can against the dull condition of bourgeois provincial life by paving the only path she can imagine towards liberation.

6. Lydia Bennet, Pride and Prejudice, Jane Austen

Although Elizabeth is generally regarded as the nastiest Bennet sister, Lydia perfects the art of disgrace by running off with George Wickham, a man with no desire to commit. Blinded by a naive conflation of lust and love, Lydia is the nasty woman we all, admittedly, can be.

7. Princess Elizabeth, The Paper Bag Princess, Robert Munsch

From the ashes of a dragon's fiery blow to her closet, Princess Elizabeth finds a paper bag - a makeshift dress she dons to return to her beloved prince. The prince takes one look at her and yells, "You are a mess! Come back when you are dressed like a real princess." The Paper Bag Princess shrugs and retorts, "You are a bum," owning her nastiness like no other fairytale princess.

8. Hermione Granger, Harry Potter series, J.K. Rowling

Hermione Granger's sharp, bookish wit and unparalleled intelligence intimidates her Hogwarts classmates, who quickly label her as "bossy" or a "know-it-all." Little did they know her nasty ambition would lead to the eventual defeat of Lord Voldemort.

9. Josephine "Jo" March, Little Women, Louisa May Alcott

Jo is by far the most ambitious of the March sisters, even if her unpredictable temper sometimes leads her into trouble. Rejecting Laurie's proposal to pursue a literary career in New York City, Jo fearlessly defies the expectations of nineteenth century women coming of age. Jo isn't heartless though - she's just an independent woman with the world at the end of her sometimes nasty pen.

10. Chris Kraus, I Love Dick, Chris Kraus

As Leslie Jamison wrote, Kraus insists through the "hyperintellectual, hypersexual" world of I Love Dick, that "all sorts of experience - even romantic obsession, dependence, and desperate pursuit - stereotypically 'female' states of abjection - hold universal significance." What begins with a "conceptual fuck" ends in a nasty takedown of the patriarchy, defying outdated ideas of "who gets to speak, and why."

Stay nasty, ladies. LSP