FESTIVAL ALBERTINE: DAY FIVE

/By Emily Lever, Tricia Woodcome, Cerise Maréchaud and Prune Perromat with special thanks to French Morning

Every Name in the Street

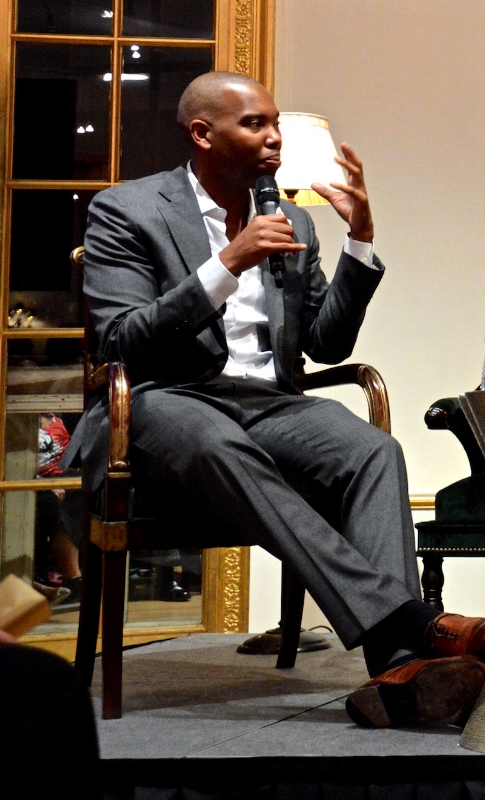

Moderator: Adam Shatz Panelists: Claudia Rankine, Zahia Rahmani, Charles Robinson, Jacqueline Woodson

Only days before a potentially world-altering election, Albertine Festival’s last literary panel tackled the political responsibility of language.

Adam Shatz, a writer for the London Review of Books, moderated the panel “Every Name in the Street,” featuring novelists Jacqueline Woodson, Charles Robinson and Zahia Rahmani and poet Claudia Rankine.

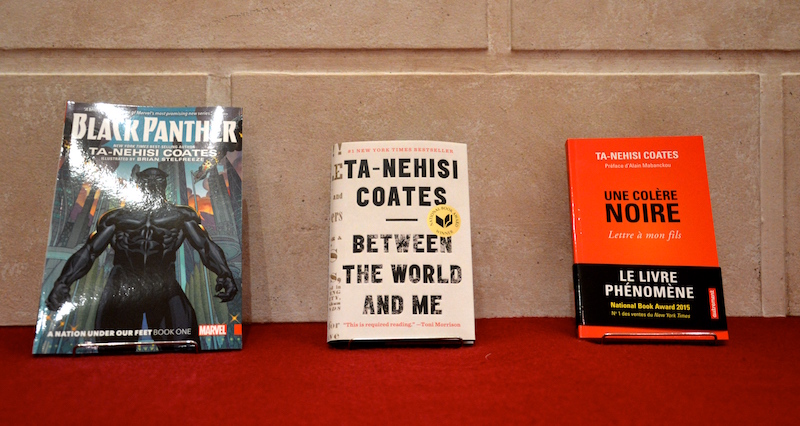

Shatz opened with the question, “what sort of weapon can language be against linguistic and actual violence?” For the panelists, linguistic violence occurs when the language of the elites is accepted as a legitimate mode of literary expression and the vernacular isn’t. Ruefully, Woodson recalled hearing Ta-Nehisi Coates’s pronunciation of the word “ask” as “aks,” a rare thing to hear in literary circles, and “mourn[ing] the fact that [she] had forgotten how to speak” in her native vernacular.

Robinson, in the tradition of American novelist Zora Neale Hurston, advocated for a “reconfiguration of language” into a modern, multicultural idiom “more beautiful, more powerful than the classical state of the language. ”

The panelists dissected what people really mean when they demand stories that are “universal.” Rankine pointed out the double standard by which some writers’ personal narratives are classified as universal and others’ as unrelatable: “Whiteness makes the world in its image and calls that universal.”

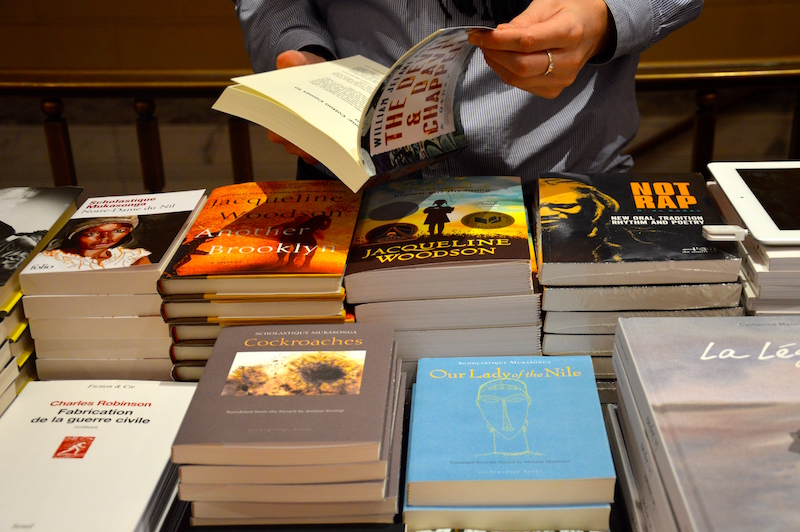

Universality was not the experience of Rahmani and Woodson, who were both motivated to write by not themselves represented in the stories they read growing up. But Rahmani also underlined that once writers of color manage to get published, they are marginalized no matter what they actually write: “In France when you’re a writer, there are two different worlds: literature and Francophonie.” She noted that the Martinican writer Edouard Glissant, an impeccable stylist, has never been included in the “great genealogy of literature.”

These power dynamics have been in place for centuries, but as Claudia Rankine shrewdly noted, what has changed is our ability to transmit and access a wider range of experiences via technology, which allows communities to be “visible in a way never done before.”

RENDERING VISIBLE THE PREVIOUSLY INVISIBLE

JACQUELINE WOODSON: “One of the big motivators, of course, is growing up and recognizing there was an absence of oneself in the literature….and making sure that wasn’t going to happen for another generation.”

CHARLES ROBINSON: “The first focus or element of my work is to explore what we are as a suffering humanity…it’s not about looking at marginal people, as a separate entity. Literature is an opportunity to explore all of our different trajectories and to create this grand common field which is our shared humanity.”

ZAHIA RAHMANI

“I think I was searching for what I could not find.”

“I think literature is haunted by the absentees.”

CLAUDIA RANKINE

“I don’t really care about story at all. I think sometimes a narrative gets in the way of the feeling, of what it means to be human.”

THE EMANCIPATORY POWER OF LITERATURE

ZAHIA RAHMANI

"In the ‘70s, [Richard Wright’s Black Boy] helped me to emancipate myself from my family, and from the French rural context. I was twelve years old at the time, and I ran away thanks to Richard Wright.”

JACQUELINE WOODSON

“One of the greatest parts of listening to Between the World and Me was hearing [Ta-Nehisi Coates] say ‘ask’ because I realized that I had forgotten how to say it. It had been trained out of me…I had unlearned how to speak the way I had grown up speaking.”

CODE-SWITCHING AND CULTURAL APPROPRIATION

JACQUELINE WOODSON

“For people of color, especially, we’ve grown up with every representation being a white representation…we’ve had lots of windows... And not necessarily have those windows into our worlds been there.”

ECONOMICS OF PUBLISHING, SYSTEMIC DISPARITIES

JACQUELINE WOODSON

“I think publishers are realizing because of [political and social] movements and their visibility, that this, too, sells books. Because at the end of the day it’s about the economics of publishing.”

CLAUDIA RANKINE

“In America, we have 35% of the population is white men. They hold 70% of the governing positions in the United States…. The rest of us are living under what they determine should happen.”

ZAHIA RAHMANI

“The American economic system perpetuates segregation.”

“I think that without socialism, you only have a barbaric state.”

“In France, when you’re a writer, there are two different worlds: literature and ‘Francophonie’”

CLAUDIA RANKINE (Photo: Cerise Marechaud)

LANGUAGE, STYLE, AND POLYPHONY

“The richness of having come through the world with those many languages, it can’t help but become a part of the rhythm of the narrative. So everything I write, I have to read out loud.”

CLAUDIA RANKINE

“I’m using language as material to get to that which is felt but not spoken. And sometimes story helps me get there, but it’s not the story that I’m interested in.”

“It’s really about writing from the position of what it looks like, rather than what is valued, which I believe are two different things.”

CHARLES ROBINSON

“This notion of polyphony, it’s the story of minorities; it’s an issue of minorities. In fact, we are all minorities…. This polyphony of human life is the organization, is the presence of these multitudes of humanities, their stories, and their different songs. I am convinced that a society is not a location of peace, but a location of conflict.”

CHARLES ROBINSON

“This notion of becoming a great writer…there’s this underlying assumption that you have to master this language as it is meant to be spoken, and therefore to confirm an order. And that’s what we call integration.”

“I think it’s important to explore the usages of the French language – the urban, or more popular usages of this language in the suburbs – and from that point on, to invent a new state of the language that would be more beautiful, more powerful than the classical state of the language.”

“What is particular to American politics, and this is true for American writers of color, is that our ability to be artists cannot exist in a place separate from our ability to see our ability to live curtailed.”