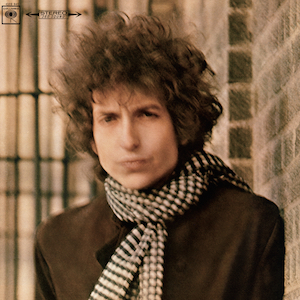

On Bob Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde

/THE COVER OF BLONDE ON BLONDE (SOURCE: WIKIPEDIA)

By Emily Lever

The Nobel committee's decision to award Bob Dylan, né Allen Zimmerman, the highest honor in literature has been controversial: not just because all of this year's Nobel laureates are male, not just because some think Haruki Murakami, Adonis, Ngugi wa Thiong’o or others were robbed, but mostly because Dylan is primarily a singer-songwriter.

Though his lyrics have been published in book form, the average person might be more likely to agree with the statement "Bob Dylan is a world class lyricist" than with "Bob Dylan is a world class poet."

Whatever you think of the smoke-filled-room politics of the Nobel, it’s hard to deny the cultural significance of Dylan’s work. His songwriting is at the crossroads of the major cultural currents of the 20th century: the sparse modernism exemplified by Dylan Thomas (who was the inspiration for Robert Zimmerman's stage name); the rabble-rousing leftism of which the American folk revival became the marching band; and the blues tradition of black American music, pilfered by popular music (including folk) for half a century, rarely acknowledged and almost never compensated.

"Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” evokes T.S. Eliot’s modernist masterwork “The Wasteland” with its fractured, impressionistic, non-linear stories told in fantastical and evocative language. "

Bob Dylan’s career has been chameleonic, so it’s hard to make general statements, however, Blonde On Blonde must be in the running for the title of best Dylan album. A song like the 11-minute closer “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” evokes T.S. Eliot’s modernist masterwork “The Wasteland” with its fractured, impressionistic, non-linear stories told in fantastical and evocative language.

Dylan didn’t wear his folk roots on his sleeve in Blonde On Blonde as much as he had in his early career, but “Absolutely Sweet Marie”’s frantic harmonica and the quintessential countercultural lyric, “to live outside the law you must be honest,” serve as a reminder that the Dylan of 1966 is the same man who recorded “The Times They Are A-Changin’” in 1964 and played the March on Washington, opening for Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, in 1963.

As for the fun, slouchy Memphis shuffle of “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat,” it riffs on the standbys of blues songwriting: repetition for emphasis and tropes of infidelity, misunderstanding, and betrayal. In blending these apparently disparate elements, Dylan gave this album a truly unique sound and poetic voice that no one has replicated since--not even Dylan himself.

Popular music, and “lowbrow” culture in general, has become increasingly accepted by critics and other gatekeepers of “highbrow” culture, especially throughout the last decade. Dylan's critical acclaim certainly owes much to how he brought a literary bent to popular music, and his Nobel prize cements the growing equality between the two ultimately arbitrary categories of “high” and “low” culture. Perhaps it even opens the door of the literary canon to hip hop lyricists like Mos Def, Nas or Rakim, who have established themselves as the poetic voices of more recent generations. LSP