A CONVERSATION WITH GERARD DEPARDIEU: AN ACTOR WHO WRITES

/French actor Gérard Depardieu, an autodidact born to illiterate parents with a furious appetite for culture, and a passion for Saint Augustine's Confessions, has been writing for decades. But his memoir-essay Innocent (Contra Mundum Press, 2017) is his first non-fiction book to be released in the U.S.

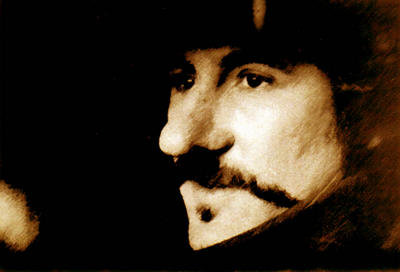

Gérard Depardieu in 1994 at Cannes Film Festival. Credits Wikimedia Commons

By Prune Perromat

Innocent's Book Cover, Contra Mundum Press, 2017 -- Design: Federico Gori

Gerard Depardieu, for many people of my generation – born in the 1980s – is like the flower on that vintage wallpaper that you grew up with. Well, perhaps not a flower, but a tree: a big tree.

He’s everything but an enigma: he’s a French actor – arguably the most famous Gallic actor on this side of the Atlantic, and around the world; he’s charismatic; he enjoys life’s many pleasures; and he reportedly can drink a zillion of bottles of red wine a day. Oh, and he pisses in bottles on airplanes too, and later brags to Anderson Cooper about it.

He’s acclaimed for a number of penetrating performances, not least his portrayal of Cyrano de Bergerac in the award-winning movie of the same name, adapted from Edmond Rostand’s famous play. The wider Anglosphere may know him better as one of the Musketeers – a less subtle role than Bergerac – in The Man in the Iron Mask, alongside Leonardo Dicaprio, or for his leading role in the 1990 American romantic comedy Green Card.

In France, where I’m from, the man is a giant – an institution. His unique blend of brutish charm, extreme sensitivity and natural panache have attracted some of the world’s best directors, including François Truffaut, Bernardo Bertolucci, Maurice Pialat, Jean-Luc Godard, Marguerite Duras, Bertrand Blier, Ridley Scott, Juan Luis Buñuel, and many others.

Gérard Depardieu in award-winning movie Cyrano de Bergerac (1990)

And since his breakout role in the cult 1970s movie Les Valseuses (Going Places), he’s appeared in roughly 200 films, occupying national and international screens every year. Lately though, despite his artistic hyperactivity, it’s Depardieu’s turbulent private life and shaky health, stormy public revolts against French taxes, friendships with Western foes such as the late Cuban leader Fidel Castro or Russian autocrat Vladimir Putin, which have attracted most of the attention.

Innocent's original book cover, Editions du Cherche Midi, France, 2015

I wasn’t sure what to expect this summer when I received his memoir-essay Innocent, which will hit US bookstands in November. For one thing, I had never read any of Depardieu’s books. Innocent was first published in France in 2015 by a well-respected French press called Editions du Cherche Midi. A quick online search revealed Innocent was Depardieu’s fourth or fifth book, his first work of non-fiction – besides a cookbook – to be published in English.

The book’s American publisher, Rainer Hanshe (founder of Contra Mundum Press) lives in Paris. Earlier this year, he happened to pass a bookstore and, peering through its window, saw a black and white photo of a half-naked Depardieu, pressing his giant belly against the top of a table – it was the cover of a book. Its title read, in big white letters: “Innocent." Hanshe was intrigued. As a publisher he has released new translations of Pessoa, Nietzsche and Rousseau; his house specializes in the publication of “works that have not yet been translated into English, are out of print, or are poorly translated, for writers whose thinking and aesthetics are in oppositions to timely or mainstream currents of thought, value systems or moralities”. When he opened Innocent – a word that comes from the latin in nocere and means "not to harm" – he saw a possibility.

His book might not be flawless, but Depardieu has a voice. Innocent is rough, unpolished, almost violent sometimes, but it clearly comes from the depths of a man’s soul – a soul on a perpetual quest to find the meaning of life, to better understand others and himself.

Born in 1948 to illiterate, working class parents in the provincial town of Chateauroux in the center of France, Depardieu has always been a fighter. “I’m a bit like the cat that one wants to drown but which got out of the bag and found itself alone on a bank. I could have become a wild cat,” he writes. After surviving his mother’s attempt at abortion (with knitting needles), a childhood of absolute freedom, no formal education and involvement in petty crimes, the restless provincial kid unexpectedly found salvation in culture, and words.

He arrived in Paris a penniless teenager with speech issues – books and plays became his companions, his tutors, his guides. The Russians first – Dostoyevsky, Pushkin, Tolstoi, Maiakovski – then French playwright Racine, the Bible, Edgar Allan Poe, Lovecraft, Alexandre Dumas, and later Saint-Augustine, whose Confessions would become one of Depardieu’s most influential texts. Driven by what movie critic Elisabeth Quin has called “the furor of the autodidact,” the young Depardieu quickly broke into the worlds of theatre and film, gaining the trust of of legendary 20th century cultural figures including actor Jean Gabin and author Marguerite Duras, who took him under their wings.

In this regard, Innocent, which has sold 100,000 copies in France and has been published in five other countries, sheds an entirely new light on someone that we – or at least I – thought we knew. Throughout the book, Depardieu quotes art, theatre, music composers and films on almost at every page, making clear how essential they are to his daily life. As he told the Literary Show Project during an interview in New York, “Culture is the only thing that removes all the inhibitions of this lack of education.”

Despite his fascination with language aesthetes and his wide book culture, the man writes as he thinks: in a conversational but firm tone, which is rich in aphorisms. He sometimes uses the second person to engage or challenge critics, readers or specific targets, such as religious extremists or politicians. Embracing his own contradictions, Mr Depardieu is impulsive and unforgiving, and in Innocent he confronts a plethora of topics, ranging from his profound distrust of politics and distaste of the media, to his love for Russia and a disconcerting friendship with Putin and a defense of Russia’s geopolitical goals, to the loss of his closest friends and of his son, almost 10 years ago, who was himself a talented actor who died too young. The words here are not always easy – they’re sometimes provocative and unsettling. But they always seem cautiously chosen, weighed and balanced, conveying an utterly original voice.

“I’m not a writer,” Depardieu claims in his conversation with LSP. Perhaps, but he’s certainly a man of words. LSP

A CONVERSATION WITH GERARD DEPARDIEU, OUR TELEVISUAL SHOW

Gérard Depardieu in a conversation with LSP's host Prune Perromat in New York, before the release of his book, Innocent, this fall in the U.S. A show directed by Tatiana Khodakivska

LISTENING TO DEPARDIEU'S WRITING (AUDIO)

The following excerpt from Gerard Depardieu's epistolary first book Stolen Letters (1988) – which is yet to be be translated into English – is some of the actor's most poignant writing, demonstrating both vulnerability and universality.

BOOKSHELF ODYSSEY in BRIEF

After Gerard Depardieu's discussion with LSP, the French actor chatted on a little more with LSP host Prune Perromat about his relationship to books, and religion.

*****

The Literary Show Project: What’s your relationship to books, in your home?

Gérard Depardieu: I read several at once.

LSP: And you, reportedly, do not have a personal library at your place, right?

GD: Oh I do! They are everywhere.

LSP: Oh, from what I understood, books were like paintings and other works of art at home: they’re not there to be exhibited. You stack them against the wall and look at them whenever you feel like it.

GD: I put them on the table – there are so many books like that. Heaps of piles of books ... Above all religious books, novels.

LSP: Religion seems to be tormenting you a little bit, from what I’ve read in your book Innocent.(An early reader of the Bible, the Koran and the Talmud, Depardieu was a Muslim for two years after he arrived in Paris in the late 1960s. He also later showed interest in Buddhism and Hinduism, and publicly declared his deep interest in Saint-Augustine’s Confessions.)

GD: It does not torment me – I'm interested. It is the opposite of torment.

LSP: I feel you’ve always been on a spiritual quest though, as some chapters of your book demonstrate.

GD: [The religious thing] is fascinating. But it’s the opposite of torment, it’s there. It's “formidable.” LSP