A BOOKSHELF ODYSSEY: CLIFFORD THOMPSON'S

/By Katya Wachtel

We first met author Clifford Thompson at The Black Lives Matter Effect conference in New York, where he spoke on a panel about “Writing Black Lives: The Politics and Poetics of the Black Memoir” with editor Chris Jackson and author and critic Margo Jefferson (Negroland: A Memoir).

His own memoir, Twin of Blackness, came out 2015. He writes about jazz, film, literature and American identity for publications including The Threepenny Review and The Iowa Review, and he received a Whiting Writers' Award for nonfiction in 2013 for his book Love for Sale and Other Essays (Autumn House Press).

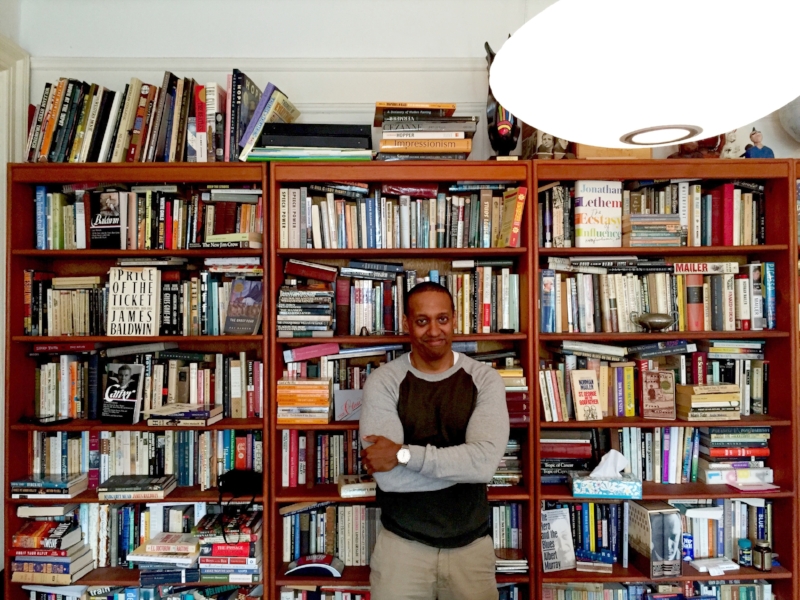

Thompson lives on a pretty, tree-lined street in Brooklyn in a building that went up in the 1920s.

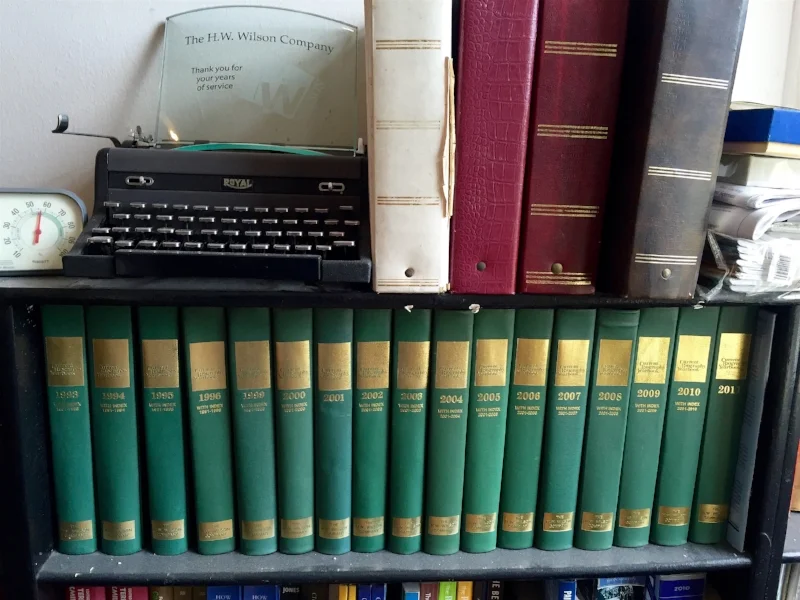

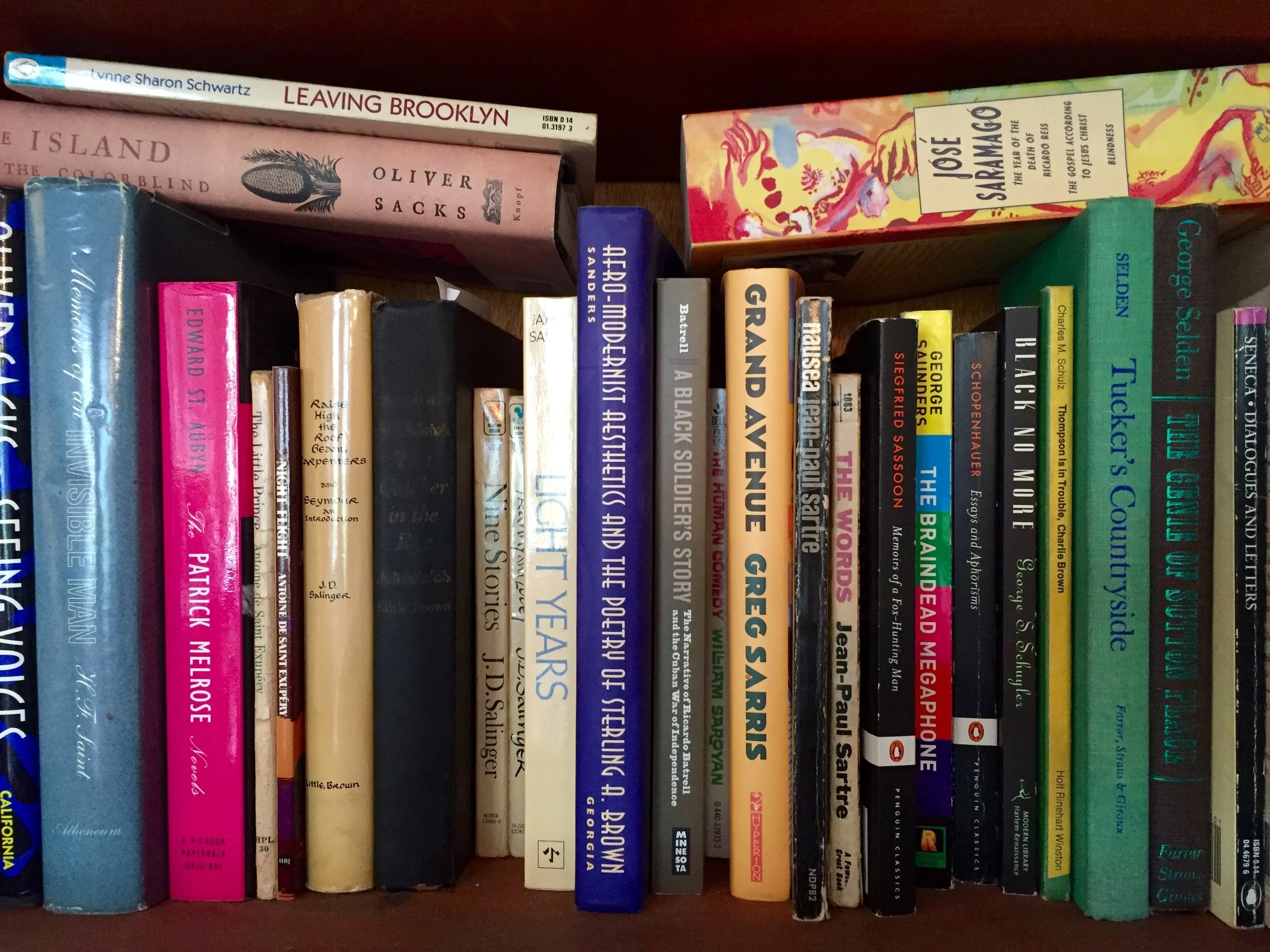

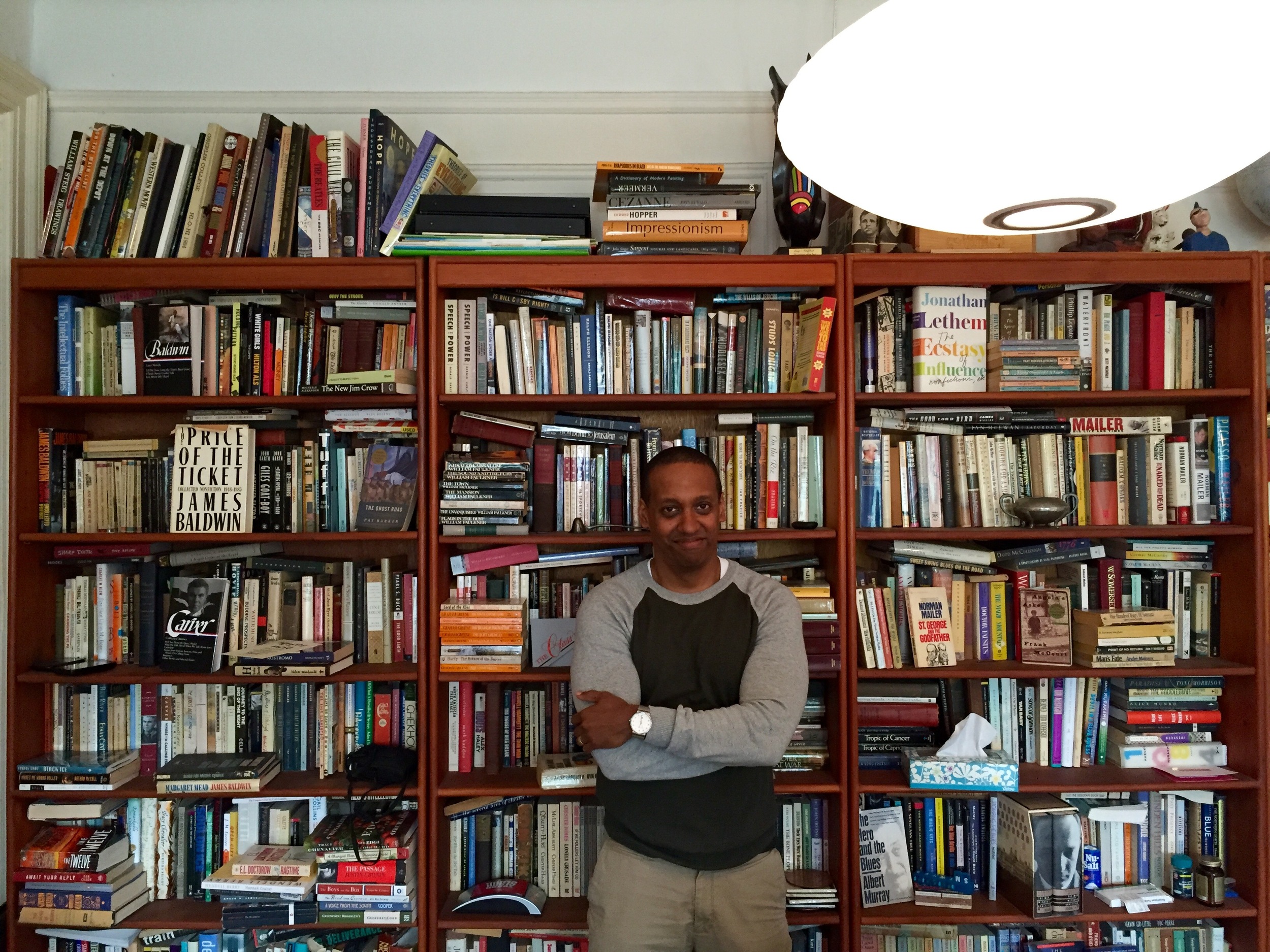

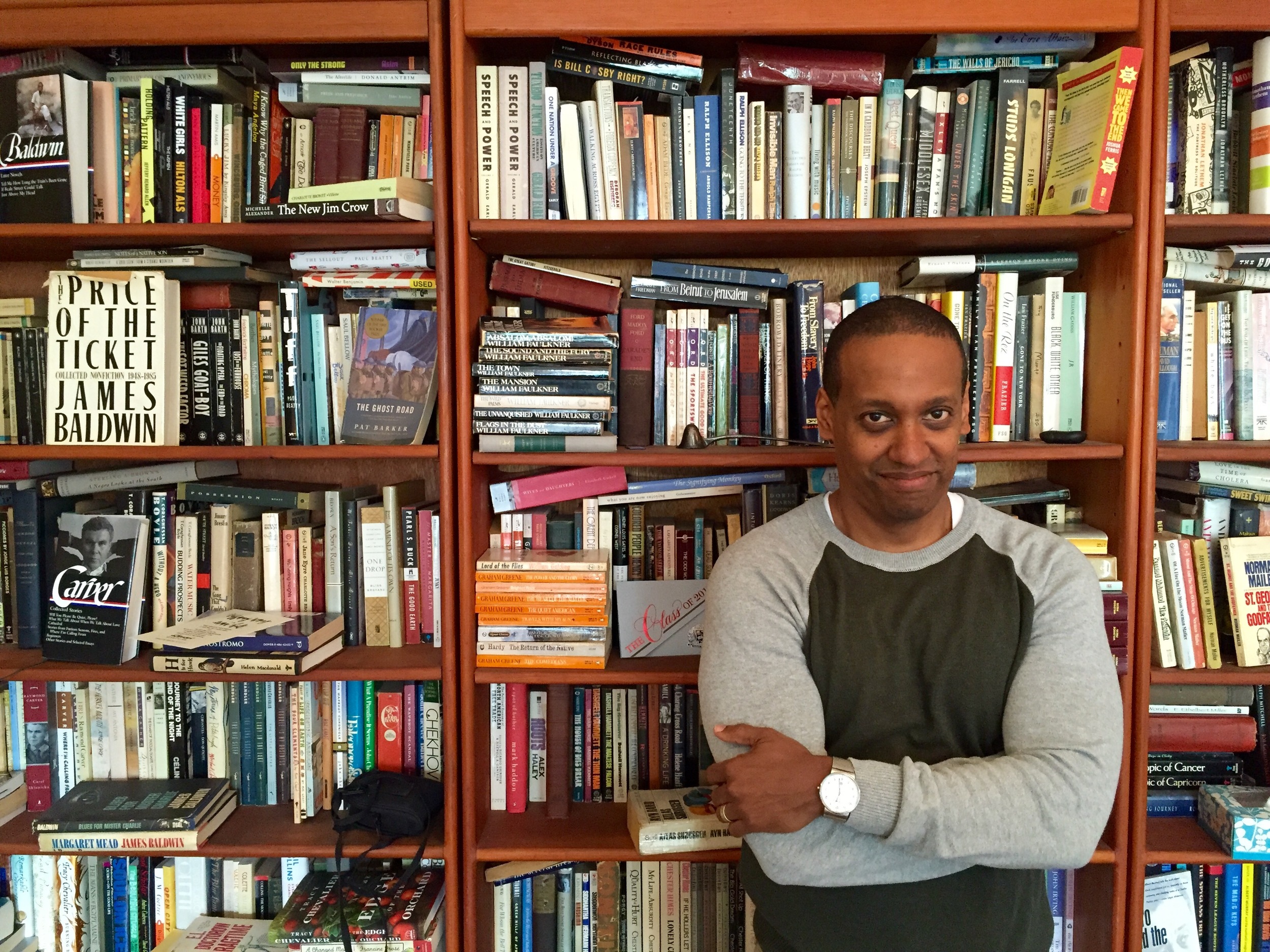

His apartment is filled with all the instruments and evidence of a writer - shelves filled to the brim with novels and hardcovers read and unread; picture postcards of authors and songwriters pinned to the wall; an Othello board game; and an old typewriter that he even occasionally still writes on.

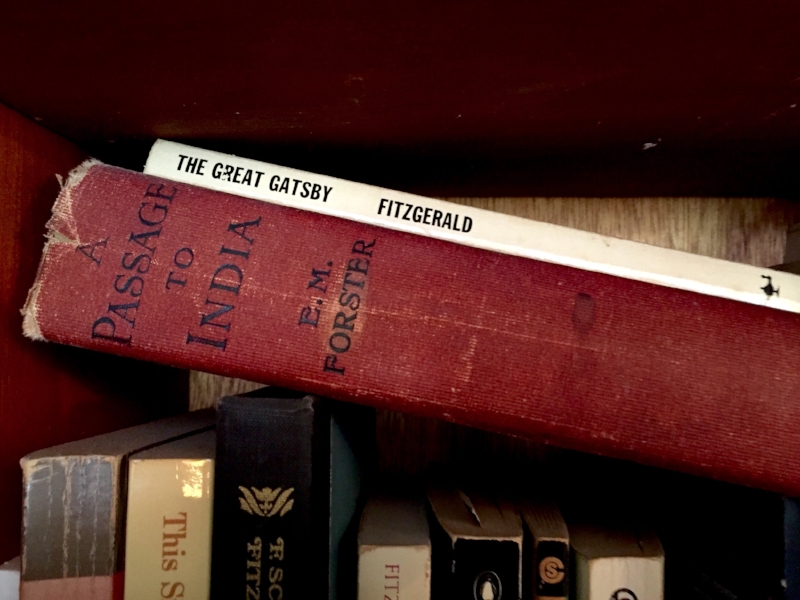

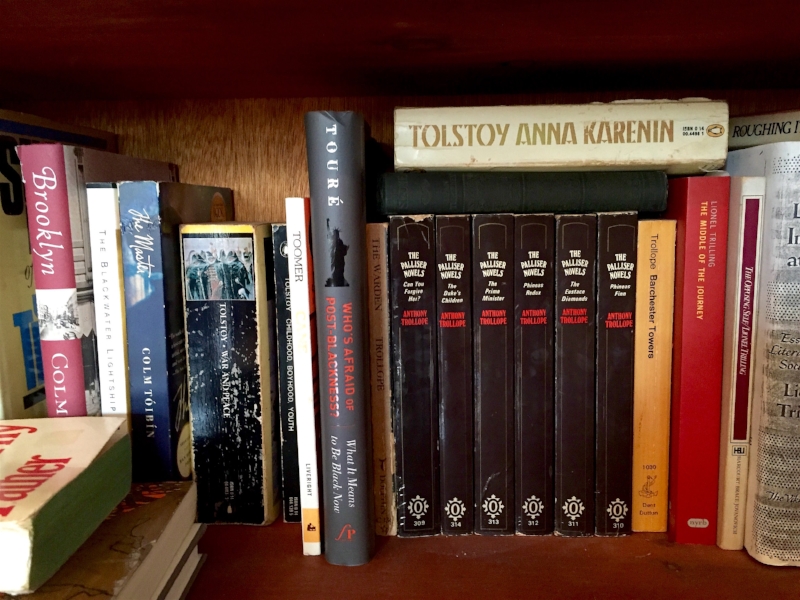

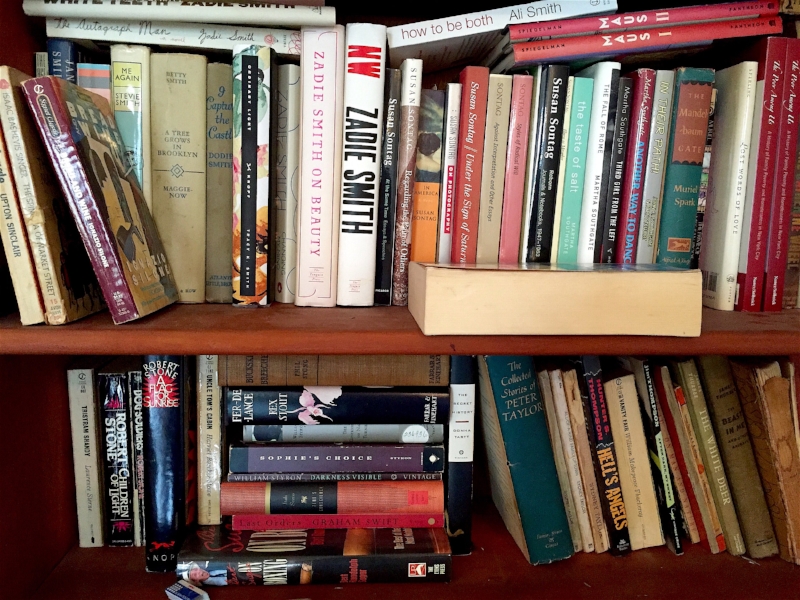

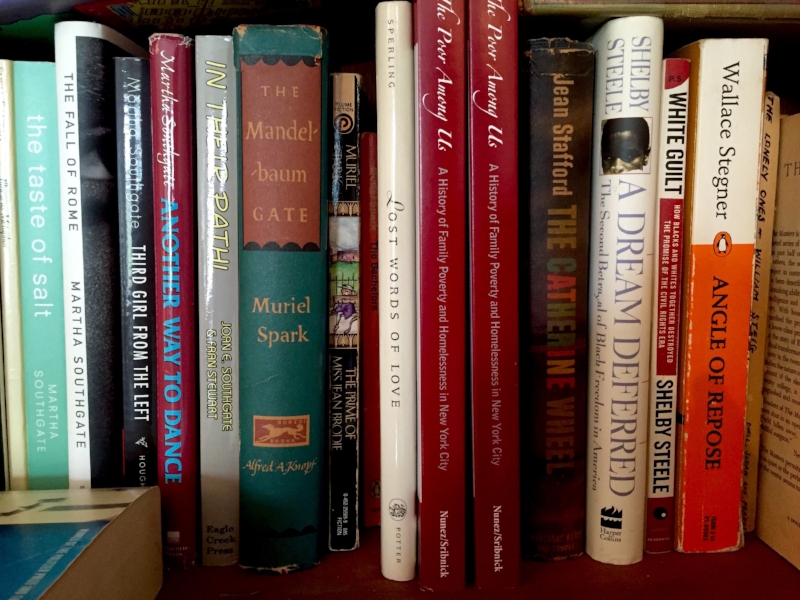

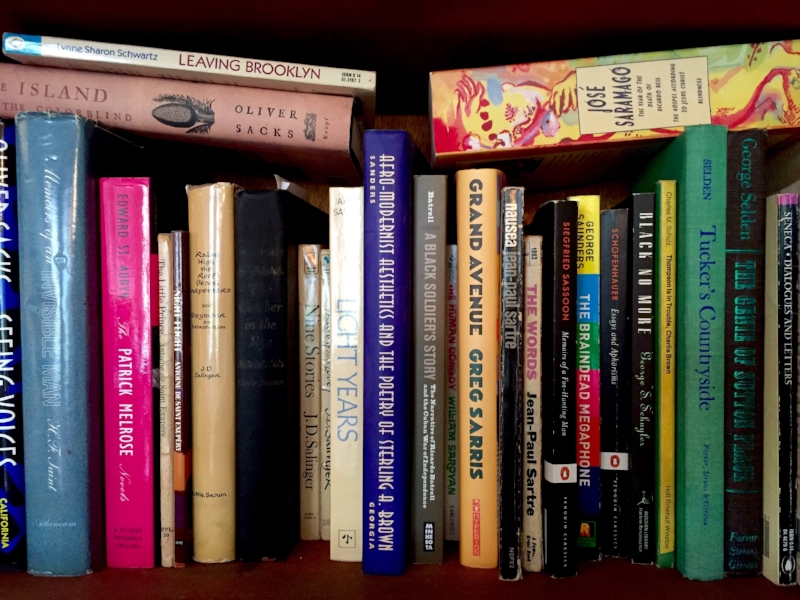

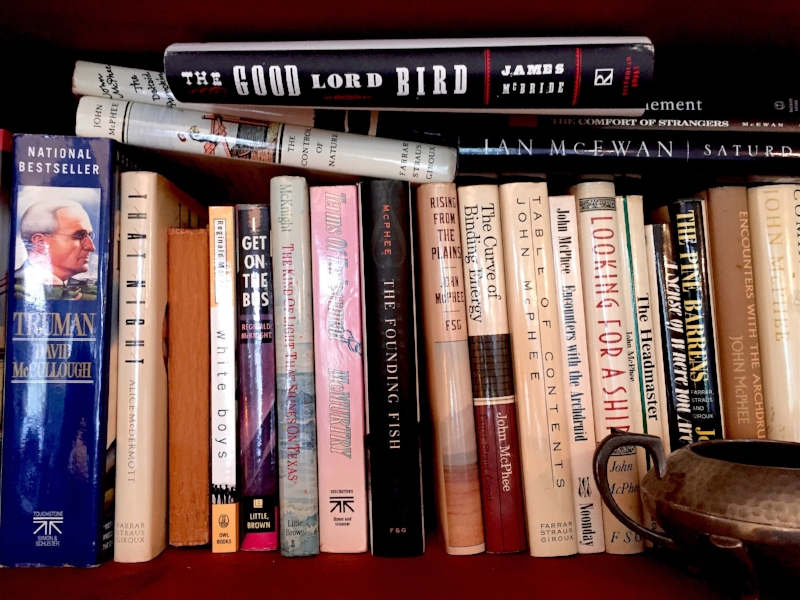

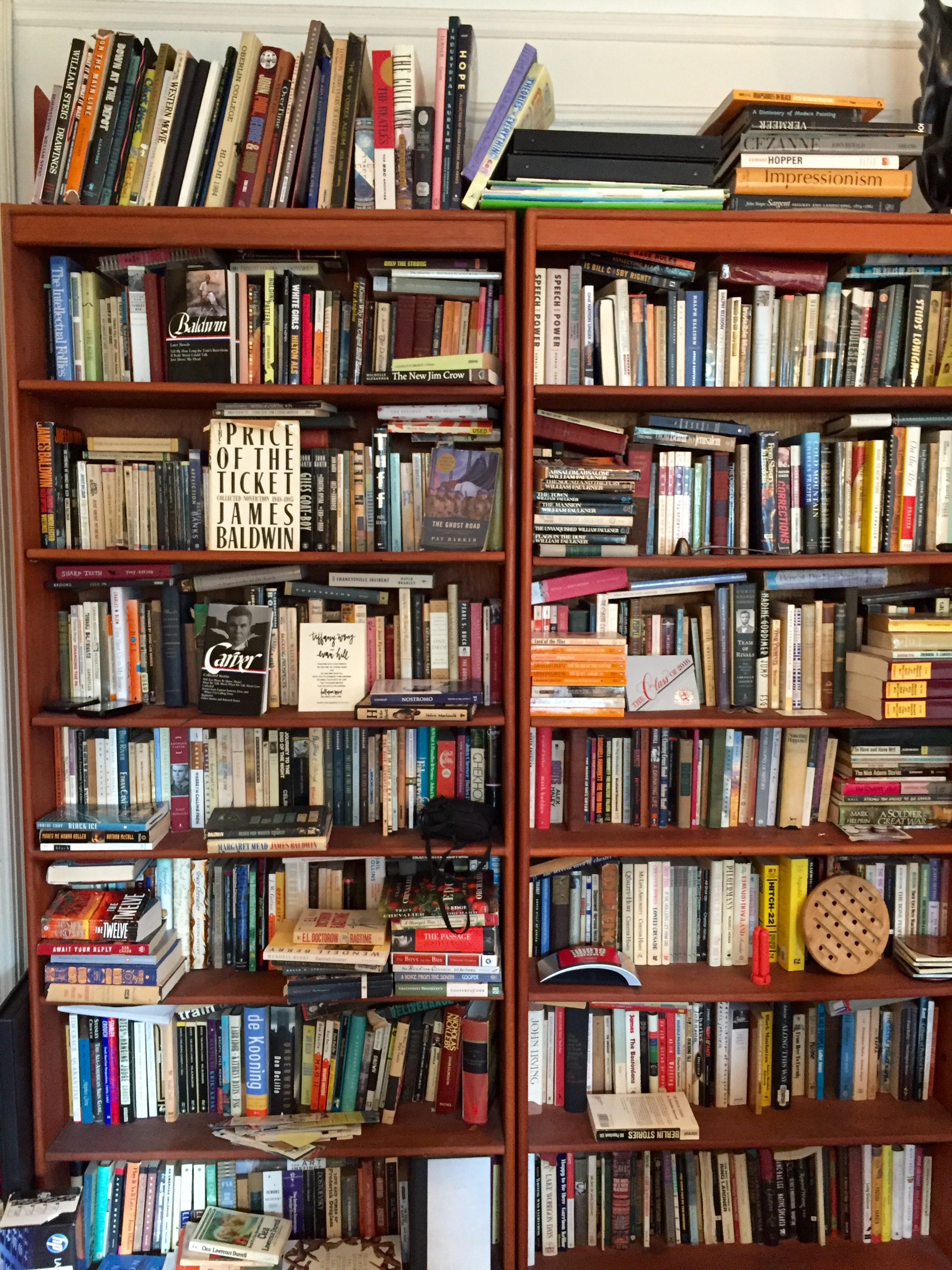

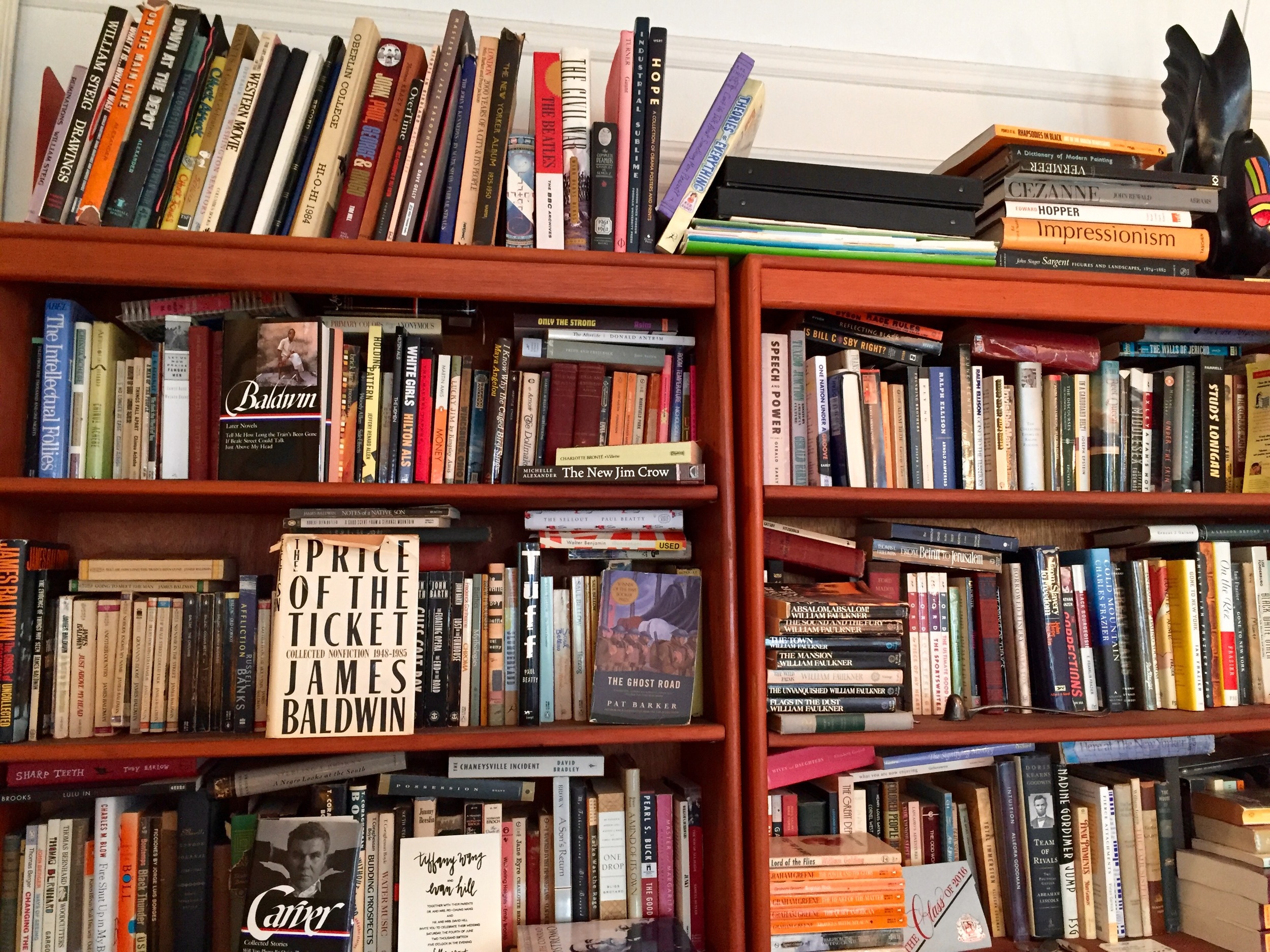

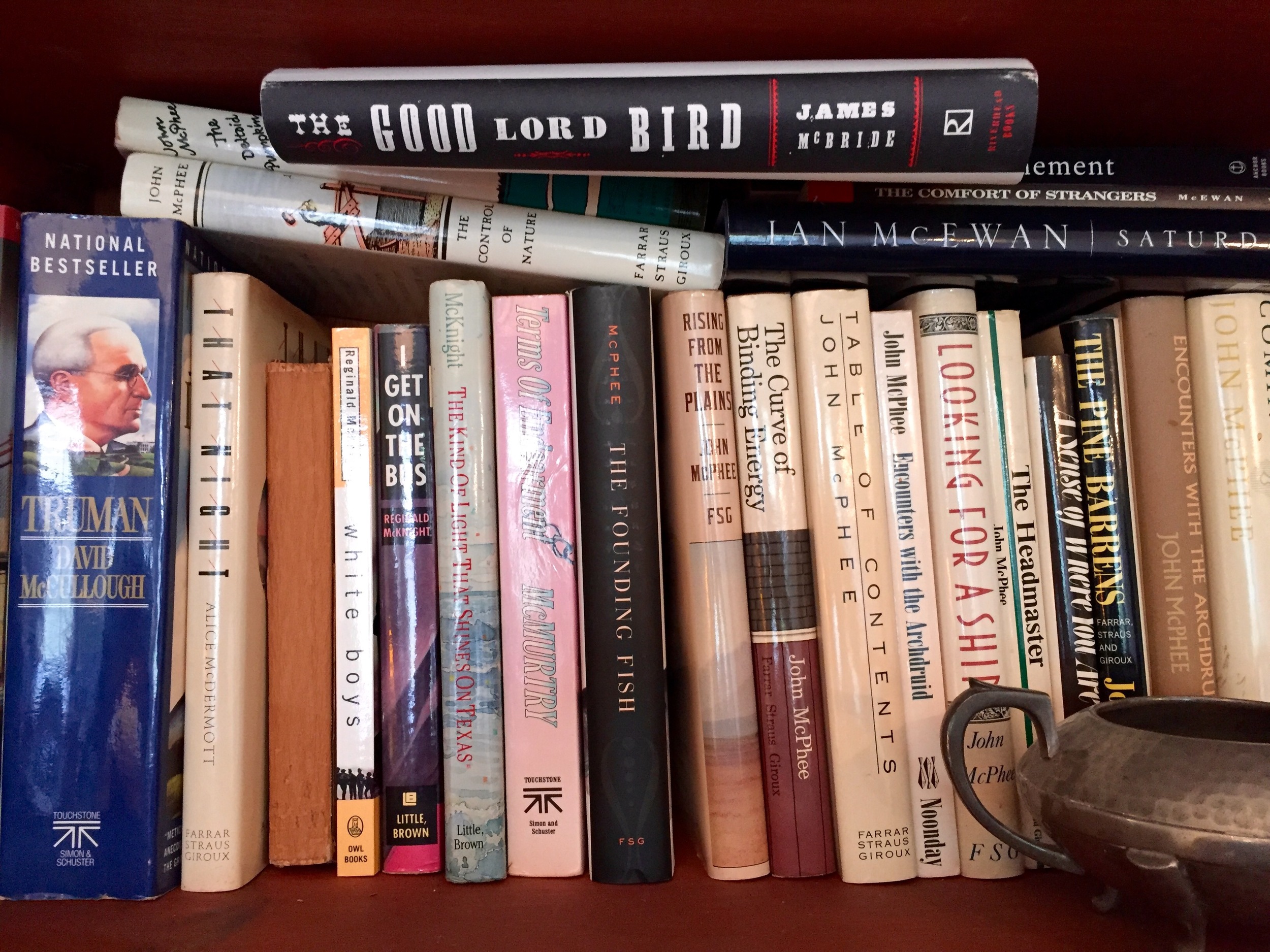

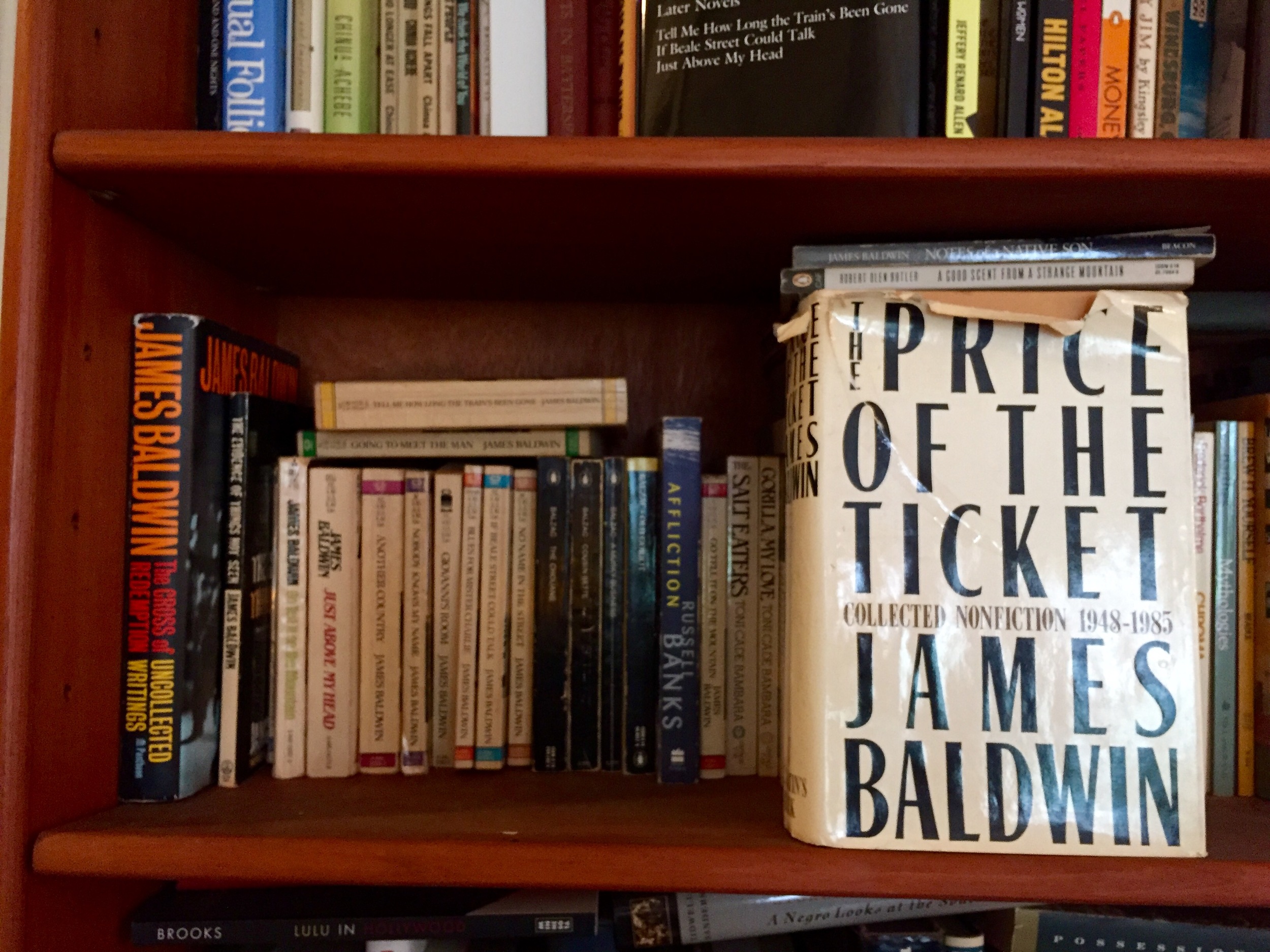

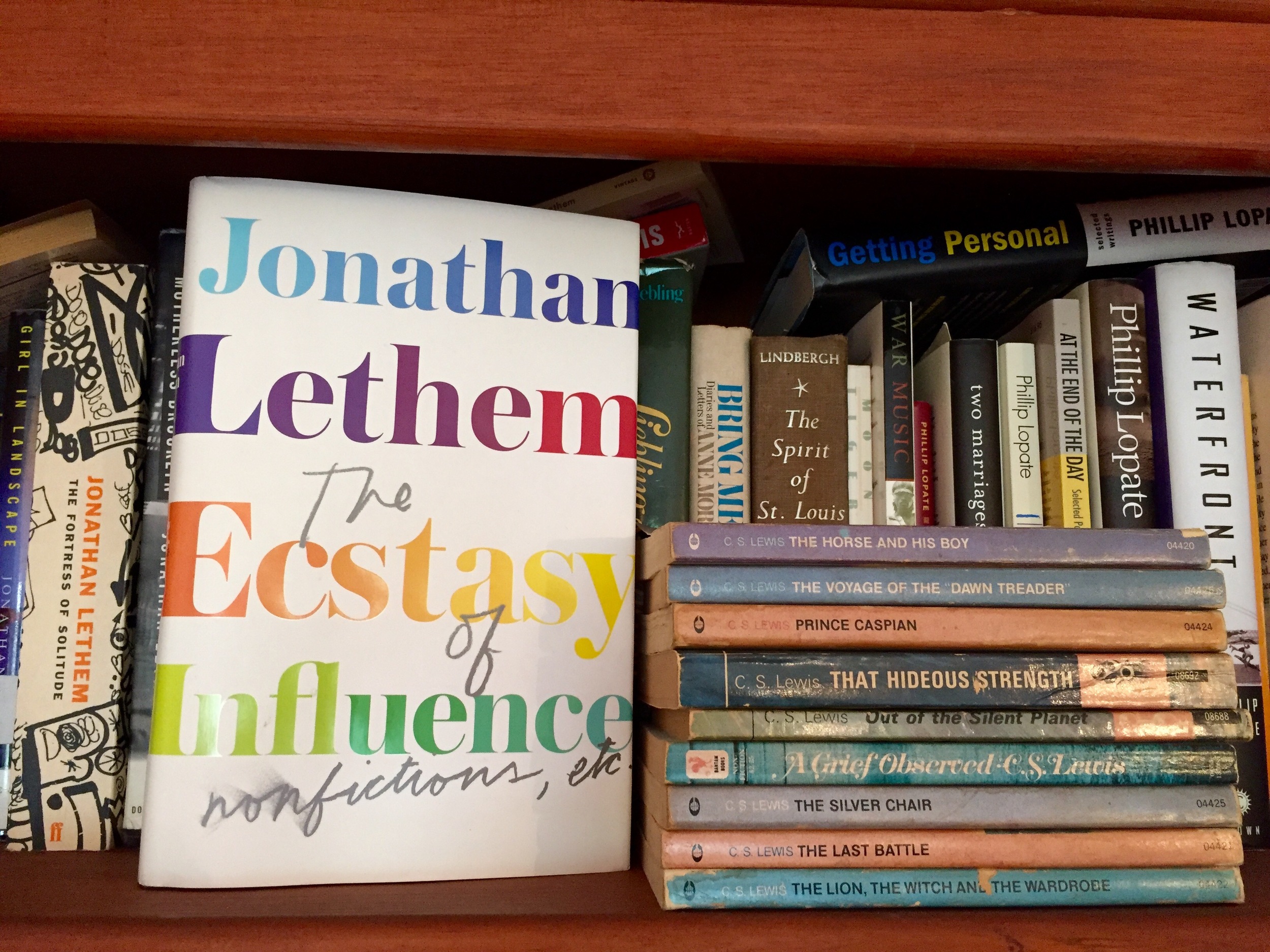

Thompson has books everywhere, but the majority of them live in four tall brown wood shelves placed against the wall in his living room.

*****

Literary Show Project: Let's start on this beautiful big bookshelf, which is overflowing with classics.

Clifford Thompson: We bought these bookshelves in the neighborhood when we moved in, in ‘91. I had my books; Amy, my wife, had her books. Her parents worked in publishing and died when she was young. So she has a number of books from them. So it's sort of three streams of books going on there.

LSP: Is there rhyme or reason to it?

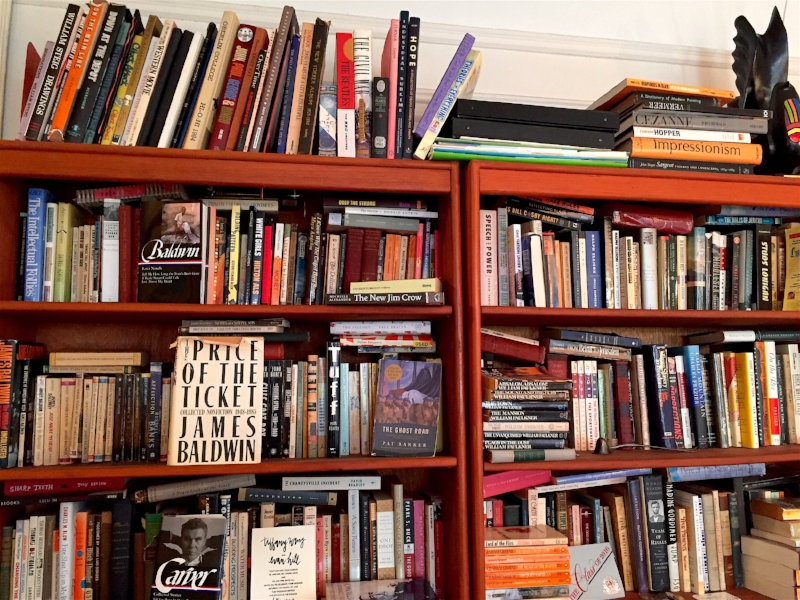

CT: It's alphabetical. Otherwise, I would have a hard time finding anything in here. The alphabetical system is really the only source of order, as I get more books, I run out of room. We have to sort of do a little culling from time to time.

LSP: So you cull from time to time? Because I have read about authors who cannot throw away anything…

CT: I am closer to that. I'd rather keep it.

LSP: It reminds me of Westsider Rare Books, on the Upper West Side. It's like this. But it's everywhere, up to the sky.

CT: I go to The Strand a lot and I love the shelves in The Strand.

LSP: What are your favorite bookstores in the city?

CT: The Strand is number one. Community Bookstore is really good, here in Park Slope. There’s Mercer Street books down in Manhattan.

LSP: Reading your memoir, you were obviously interested in music and jazz and film and TV as a kid. But in terms of a local bookstore, there weren’t any around?

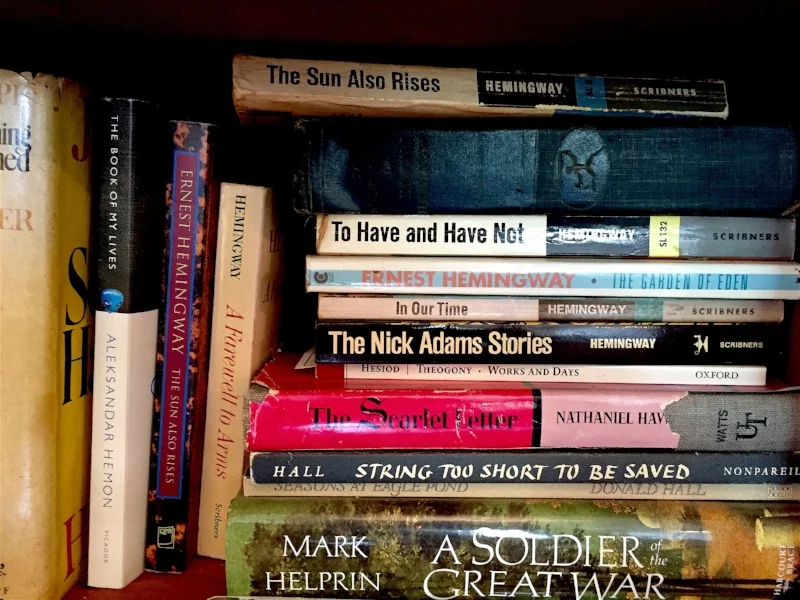

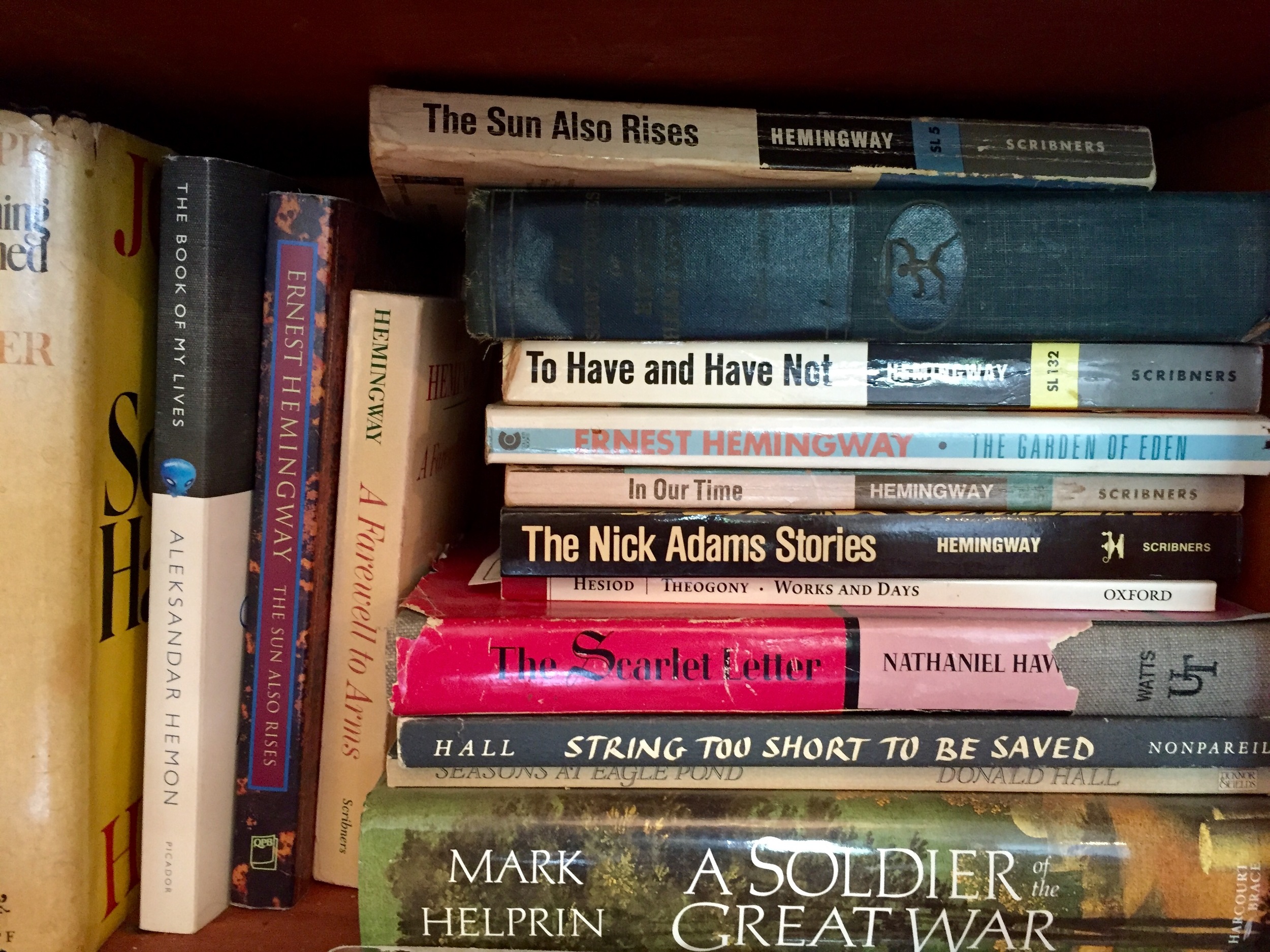

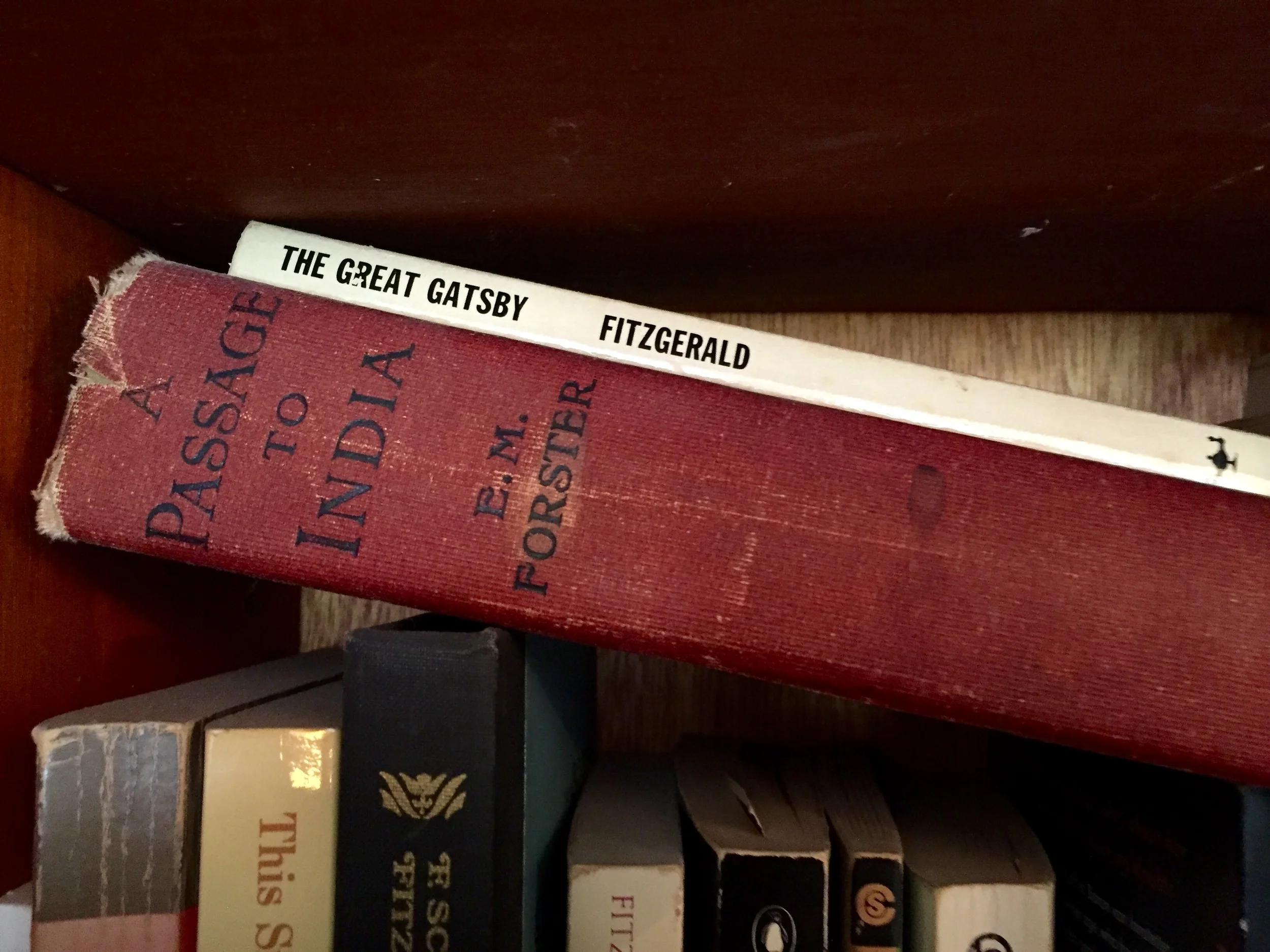

CT: You really had to get on a bus to get to a bookstore where I grew up. I will say though, I have three older siblings, and they all went to college and a lot of their books ended up in the basement. There used to be a great bookstore in Washington DC called Brentano’s. I went there and I picked up, at random, a copy of The Sun Also Rises. I didn't buy it for some reason. But then I went home and there it was on the bookshelf.

LSP: So the basement was kind of your own personal library, curated by your siblings.

CT: Exactly.

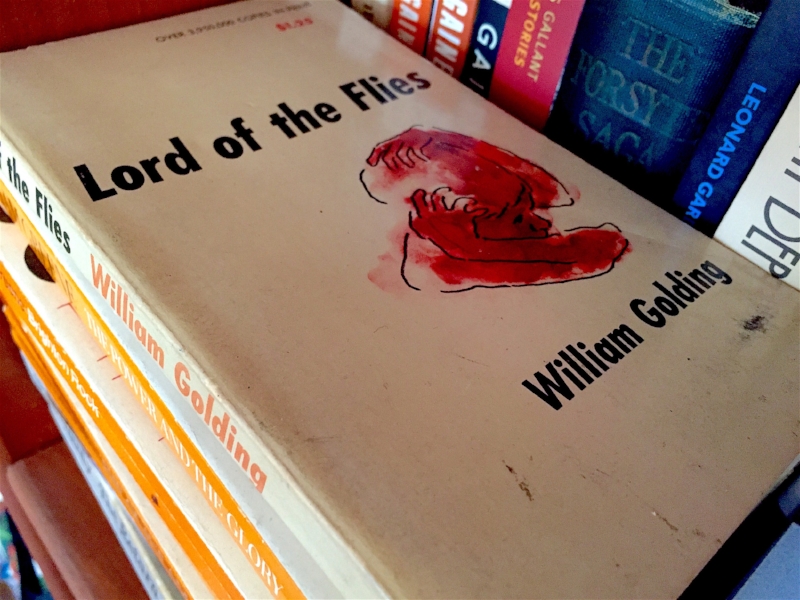

LSP: What, if you can find it, is the first book you bought? Or the one that you've had for the longest?

CT: My copy of The Sun Also Rises is the edition that we had when I was a kid. I found a copy of the very same edition on the street here. This is it. This is the edition. This is not the actual copy but it’s the same edition that I read. I was so excited when I saw it, cause I just love this one. I mean, look at it.

LSP: They don’t make covers like that anymore.

CT: No they don’t.

LSP: You obviously buy a lot of used books.

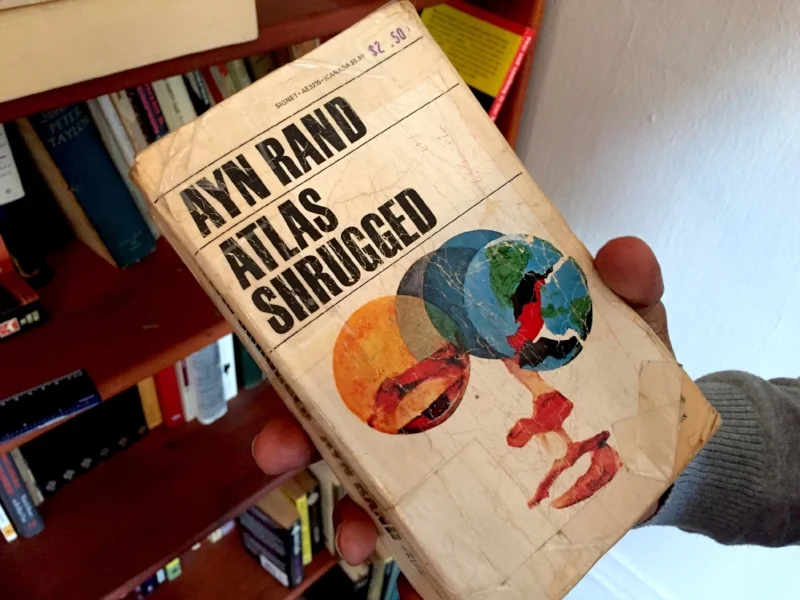

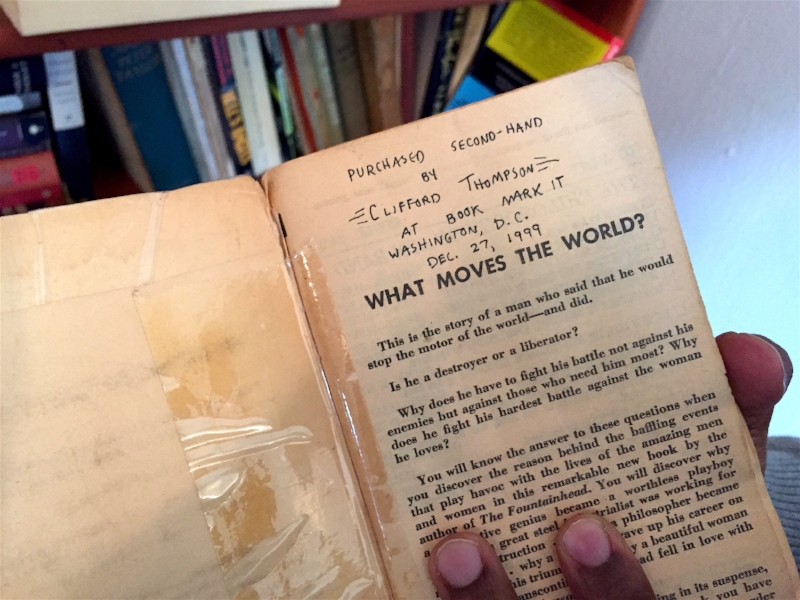

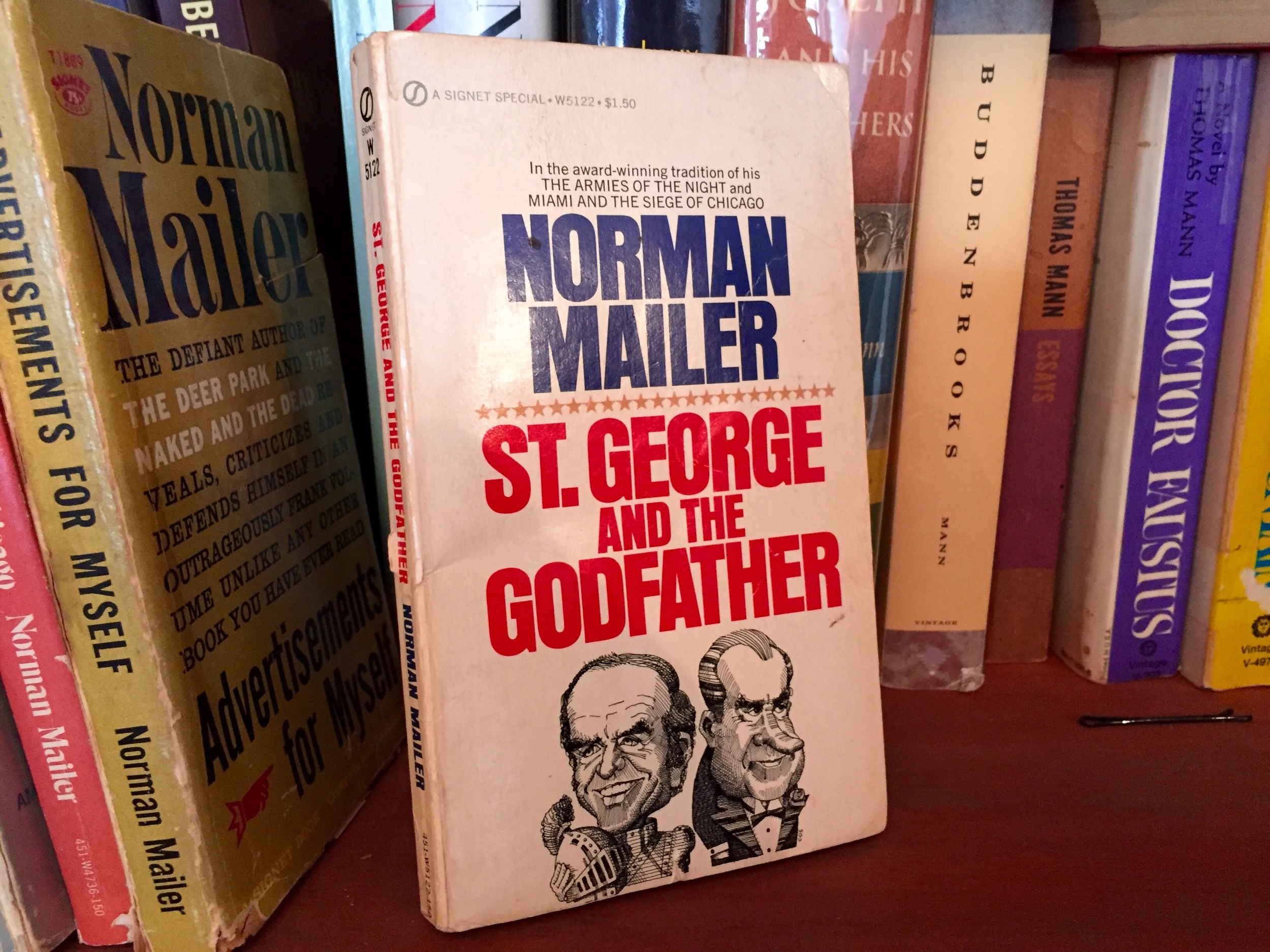

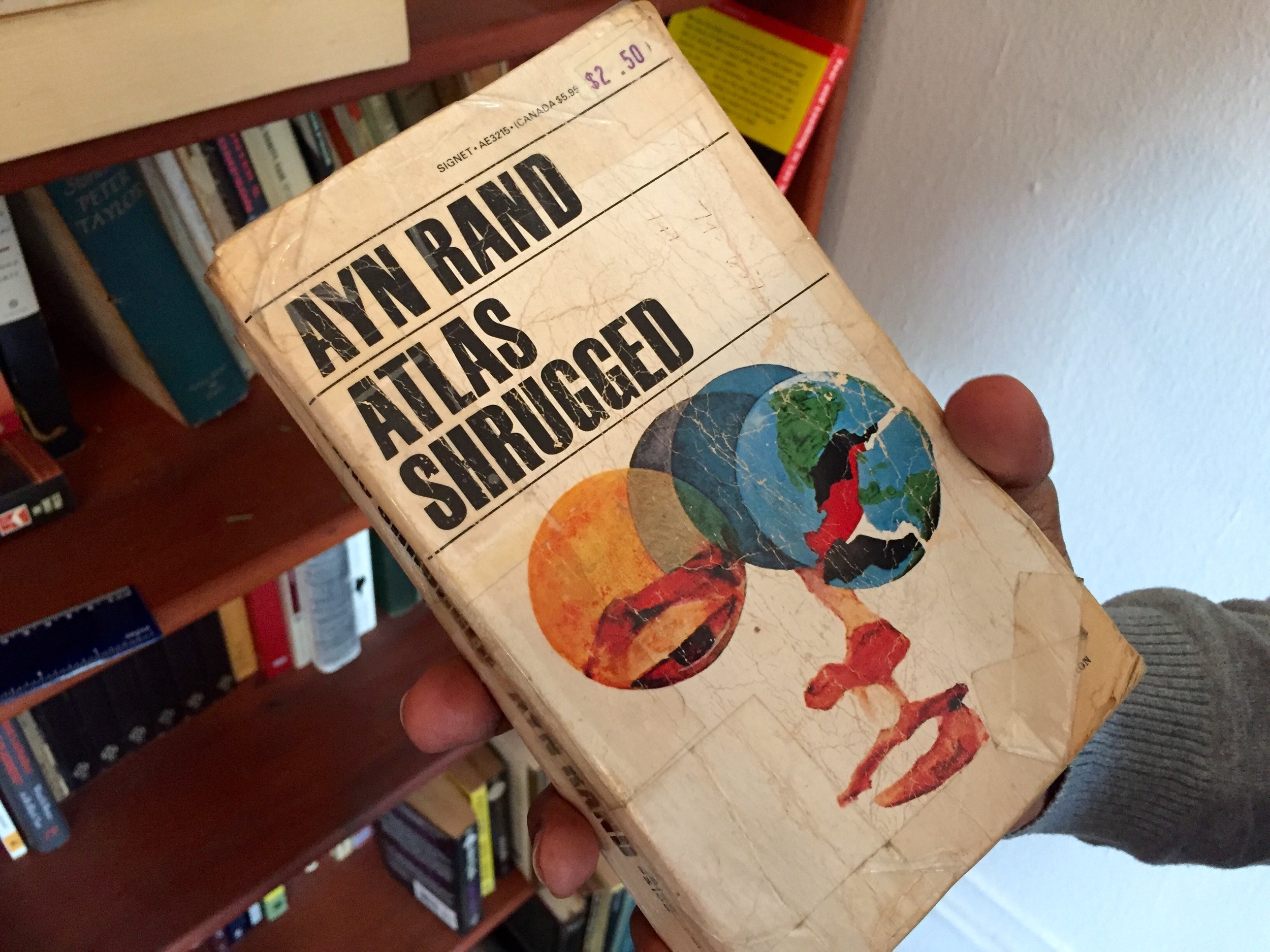

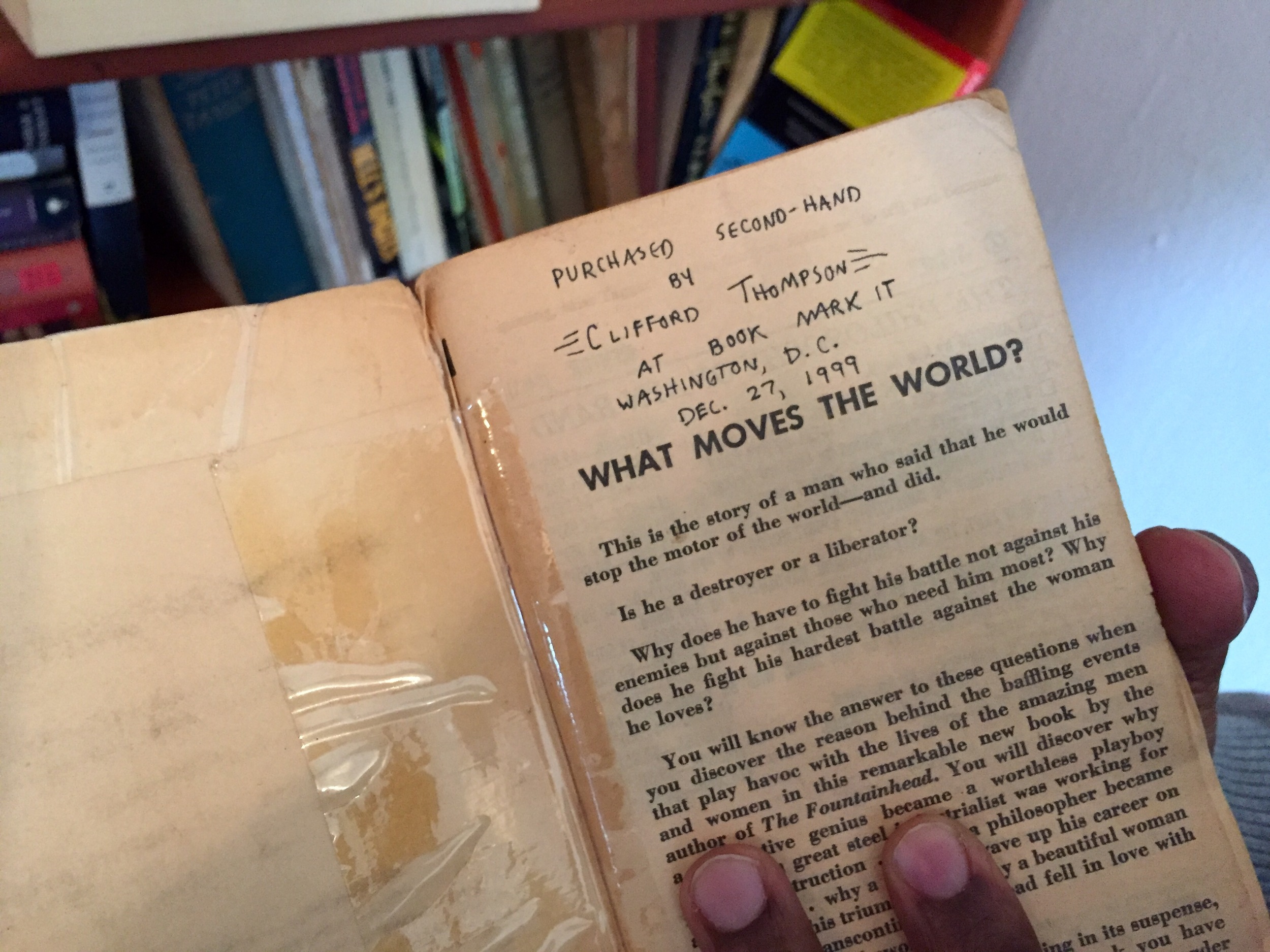

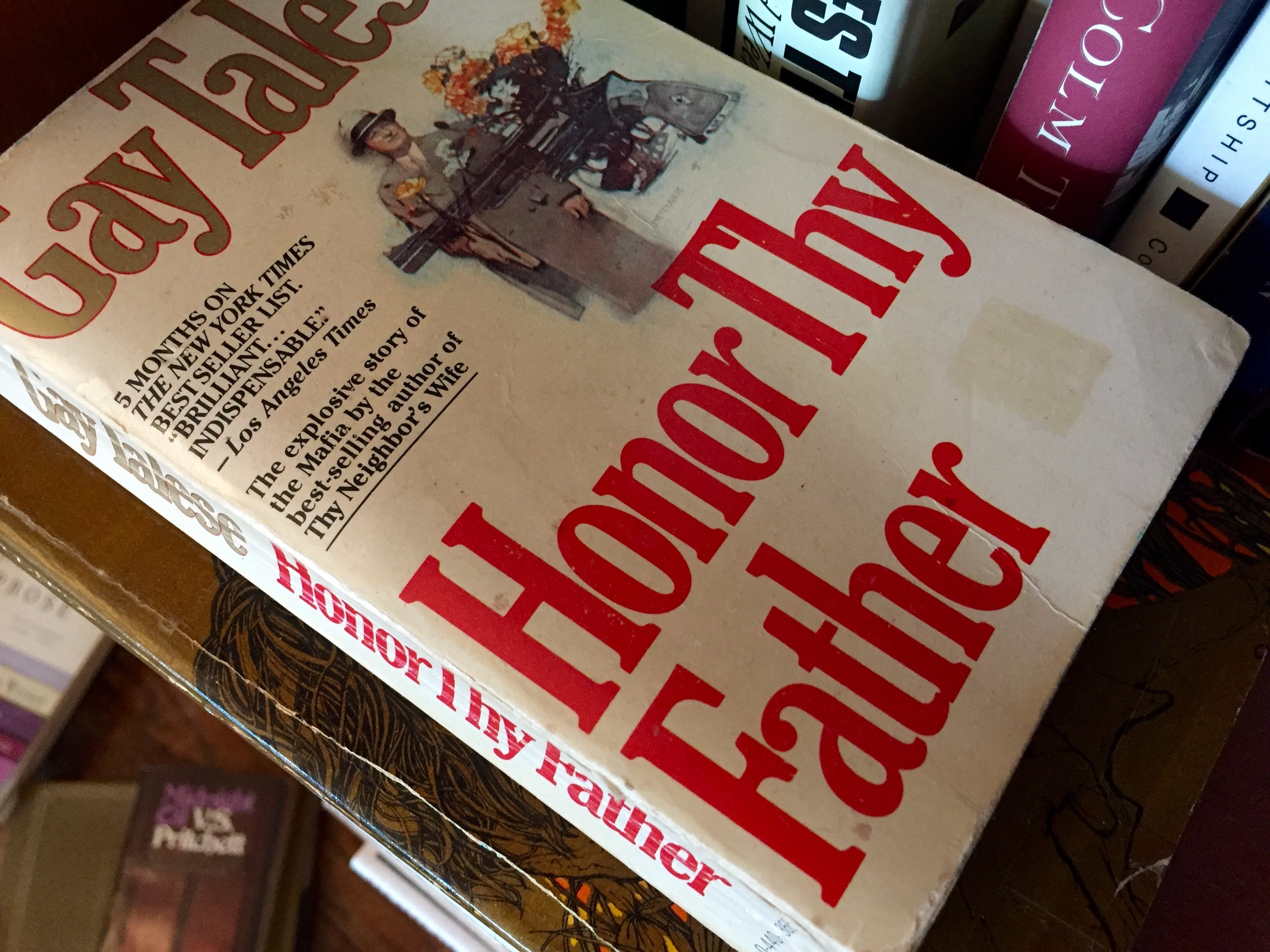

CT: Yes. I mean it's kind of a slightly silly, slightly romantic view that I take of it. This Ayn Rand, right here– The other thing I do with books is I like to write down where I got them to remind me of where I got it and maybe where I was when I bought it, which might bring back what I was thinking at the time that I bought it.

LSP: Which, for memoirist, is very important.

CT: I spent a little time getting through this - Atlas Shrugged - while I did, I had to tape it together. But it’s almost like this romantic thing of the book is like a soldier fighting a war against my ignorance. And it gets wounded and I have to patch it up.

LSP: That's the main thing about those great second hand books: you get them, you are so excited, and the minute you turn the cover, it rips.

CT: Yeah, so you have to do stuff like this.

LSP: Are there any books on the shelf that came to you via a strange story? Anything with a good anecdote?

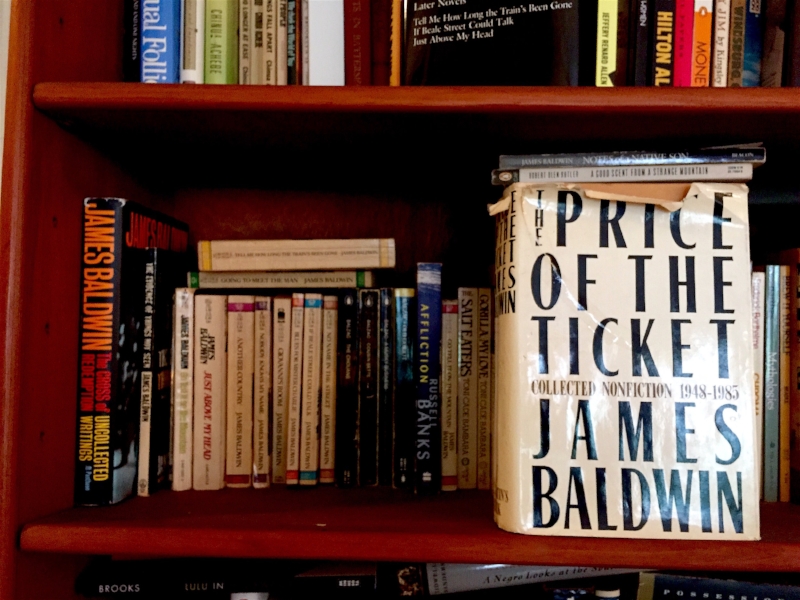

CT: I worked at Doubleday as an editorial assistant when I was in my 20s. One day – it was early December of 1987 – the editor I worked for came in to work and said James Baldwin is dead. And then he said: you and I are going to the funeral. Because he was friendly with Gloria Jones who was married to the writer James Jones, who was one of Baldwin's set in Paris when he lived there. So we went to the funeral. And I had read maybe one story by Baldwin, at the time, I think was 24. And the funeral was very impressive – all the literati was there. I think Toni Morrison was there. Amiri Baraka was there. There's a great documentary on Baldwin called The Price of a Ticket and there is a shot at the end of people coming out of the funeral. I didn't know who they were at the time. You can see Stanley Crouch, Cornel West was there.

So I came back to Doubleday, I had all this going on in my mind, and then a fellow named Gerald Gladney, who was a friend of mine, who’s dead now, he was black, he was maybe a dozen years older than me. He came by my desk one day, and he gave me these [James Baldwin books], which were published by an imprint of Bantam Doubleday Dell, and these books I have to say, changed my life. He gave me the stack of books. And he gave me a gift that I can't ever repay, basically.

LSP: Do you remember what he said when he handed them to you?

CT: Not much. He just came by. He said here, take these, basically. I took them home. They sat on my shelf for a while, and I picked them up. And then it was all over. I devoured them. And he’s been a touchstone for me ever since.

LSP: Which other books have affected you as a person, and also your writing. What are two or three that really got you?

CT: I don’t know if I can pick just one but there has to be a work of Baldwin somewhere in there, maybe Notes of a Native Son, maybe The Fire Next Time. This book here is not one of his more celebrated works – Tell Me How Long the Train's Been Gone. As a novel it's a little on the formless side, but there’s such a great meditation on interracial friendships and romances. This book is sometimes critically reviled. I found it, just personally, to be very important.

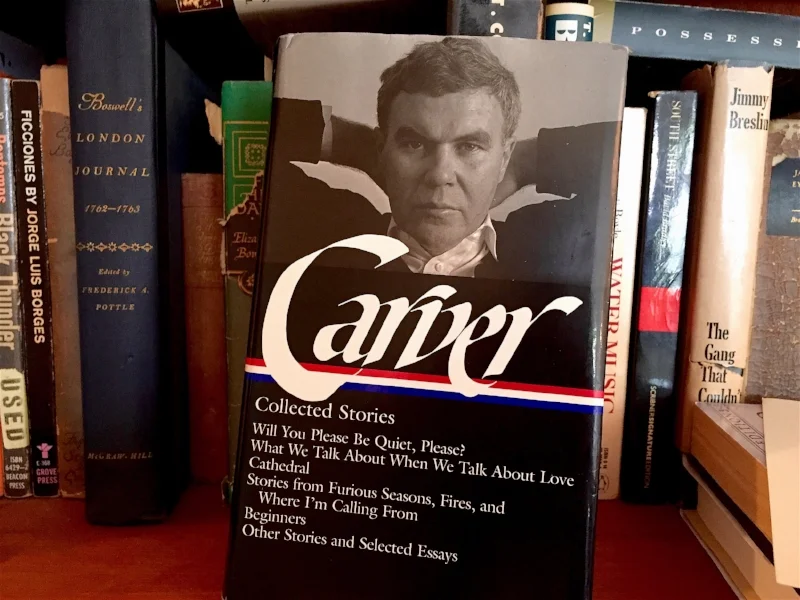

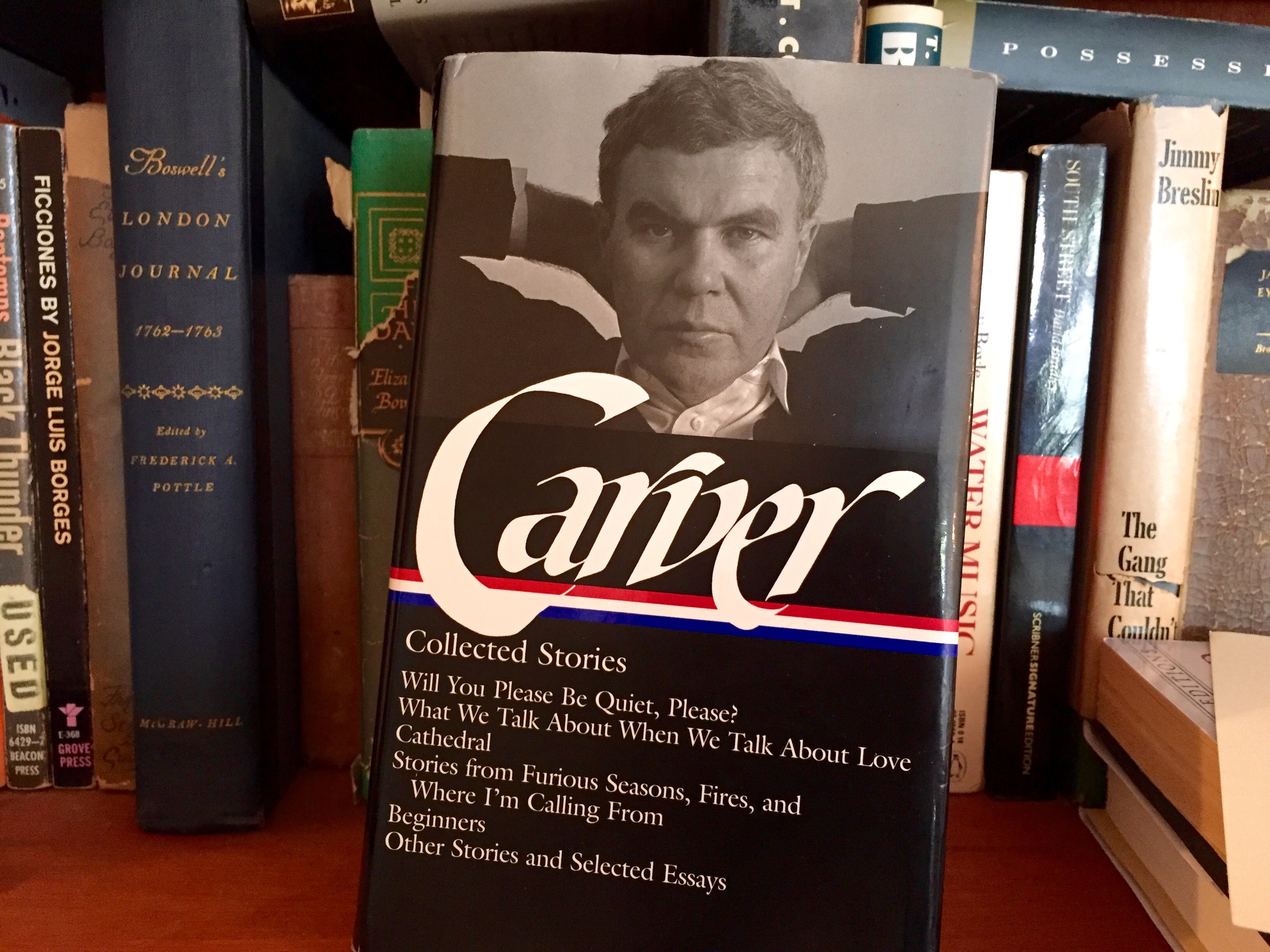

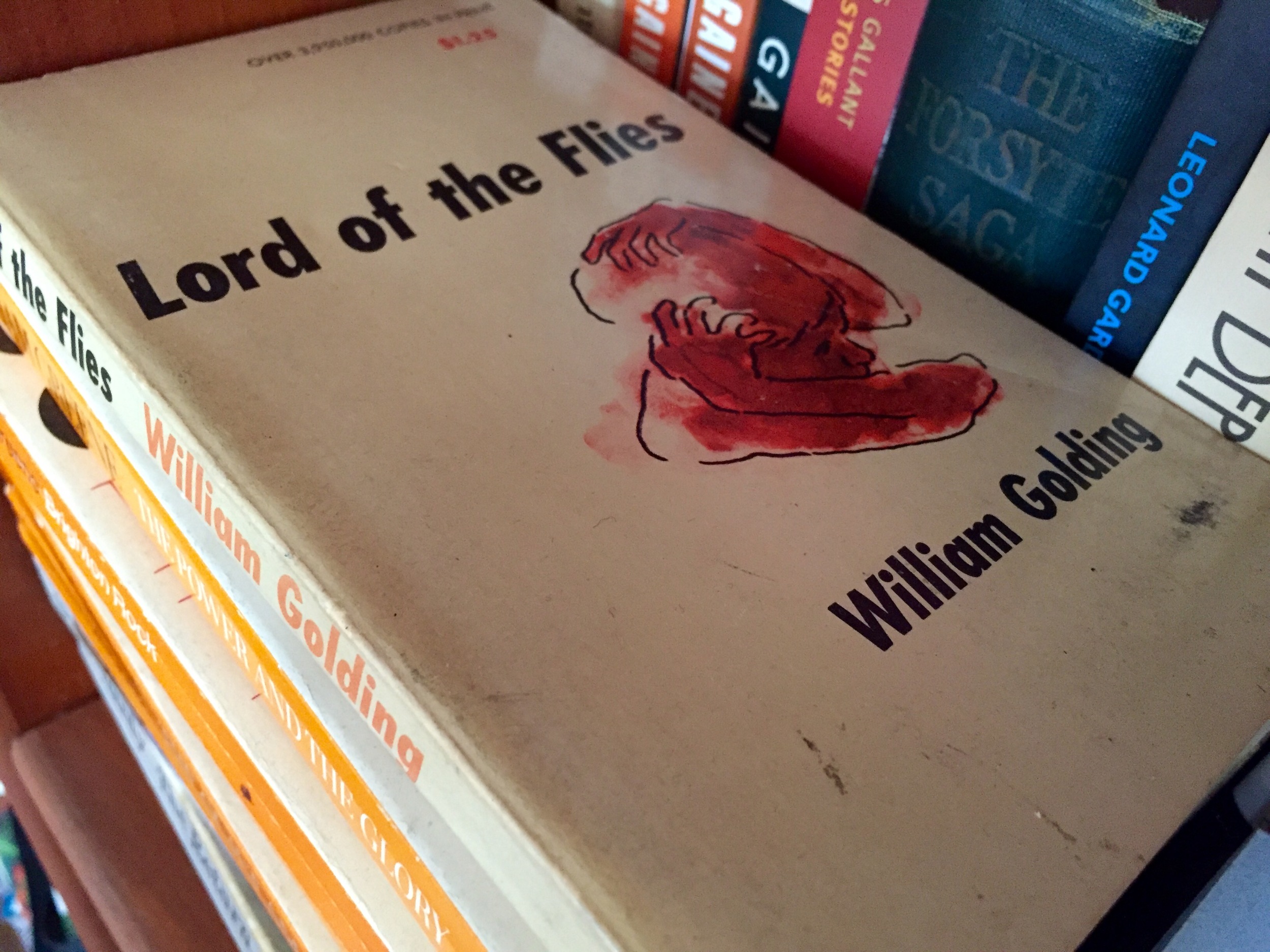

Raymond Carver. When I was in college, everybody loved Ray Carver. And I went back and read this book recently, just to remind myself of what was going on there. And it's pretty great stuff. I would say he was one of the most – if not the most - influential fiction writers of the 80s. I think he left his mark on a lot of people. And having past the age of 50 – he died at 50 – so at the age of 50 I can appreciate how young he was.

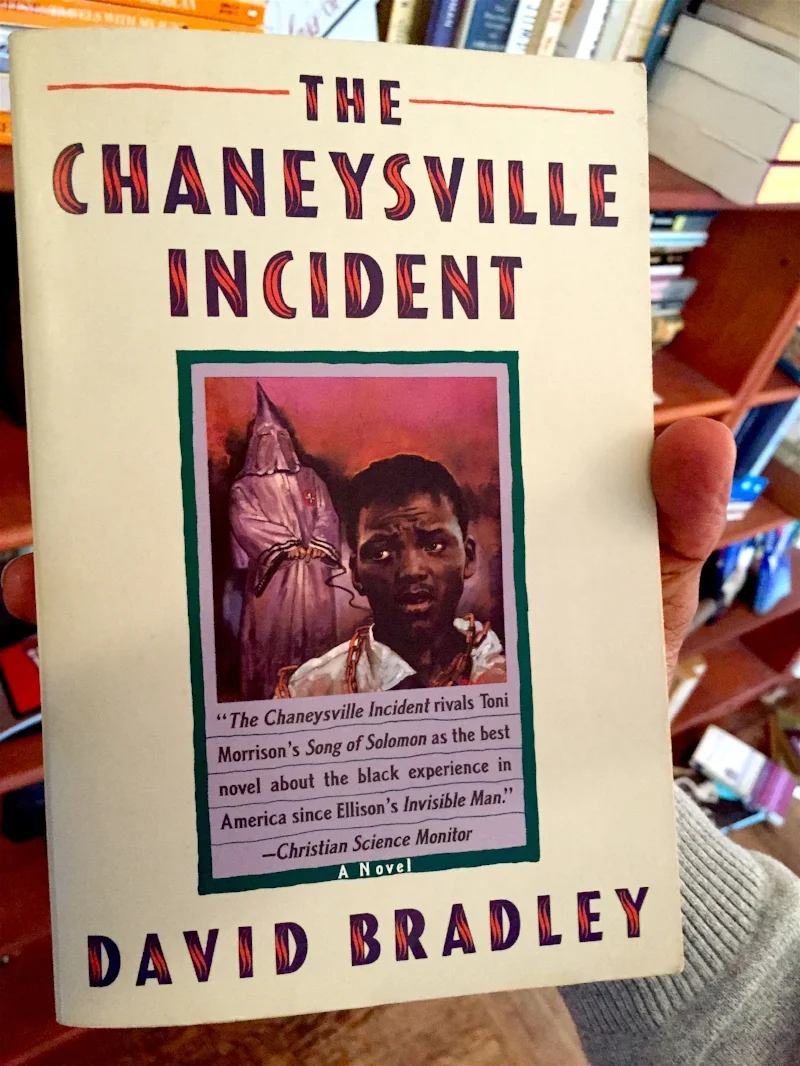

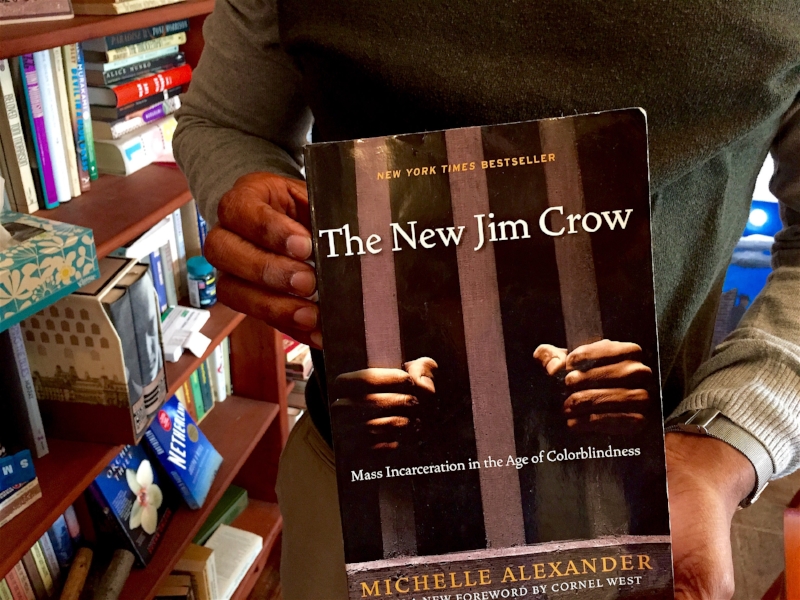

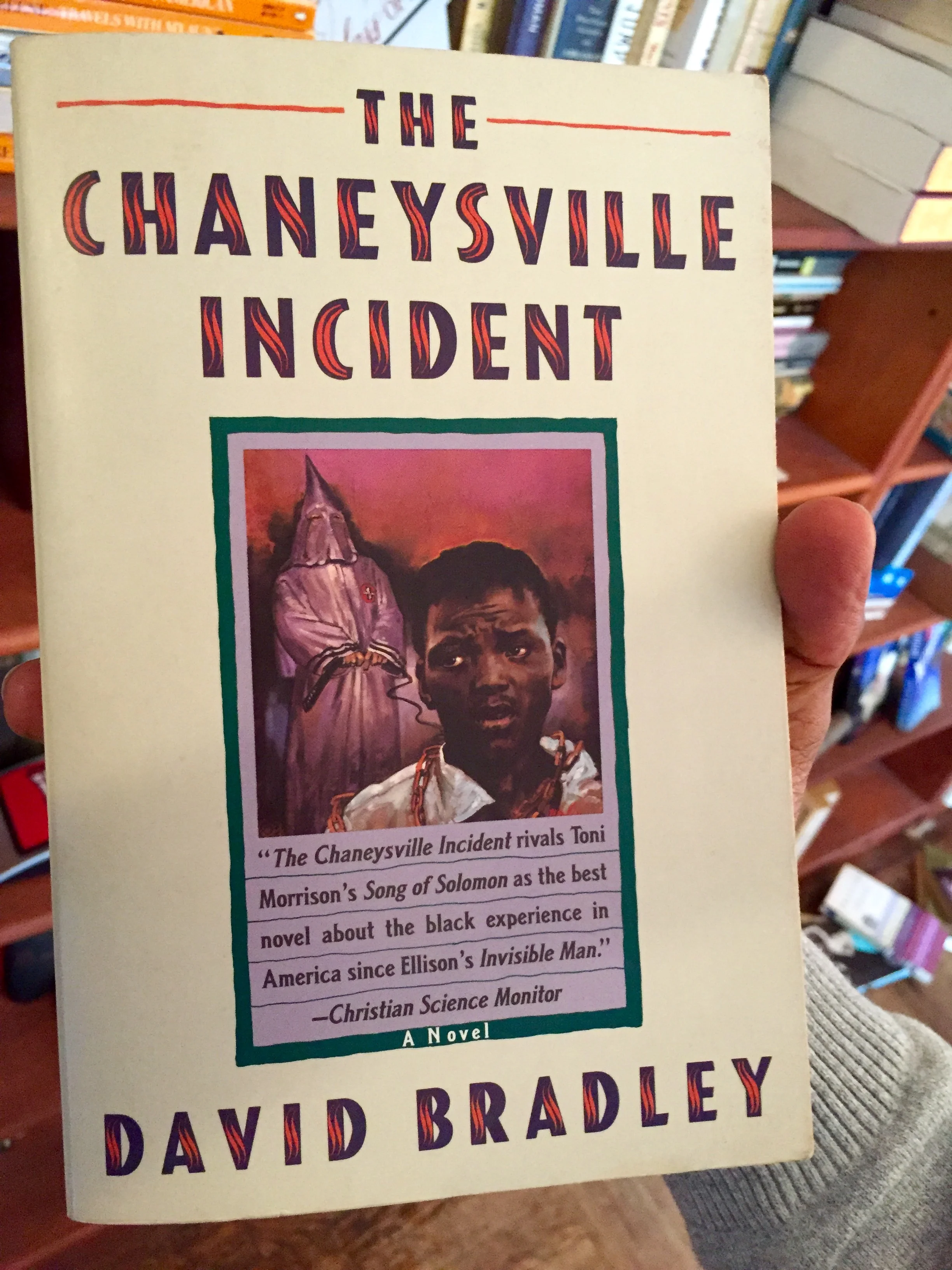

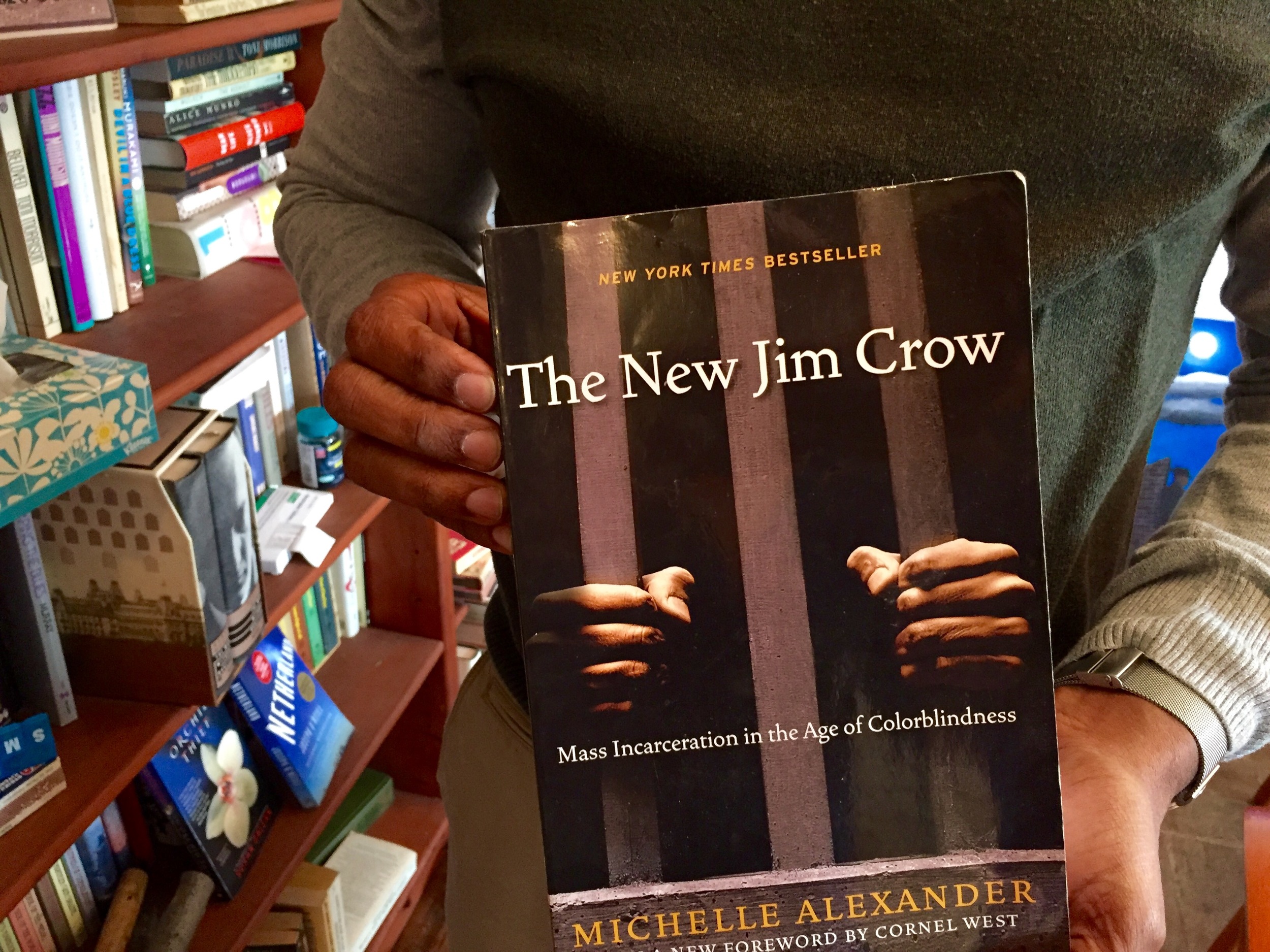

I read this maybe a year ago. The New Jim Crow, and every American ought to read that book. Just as an examination of what's going on with mass incarceration and how it's not accidental. It's a really eye-opening book. Here is one you might not know about. The Chaneyville Incident by David Bradley. This is a very powerful novel. I must have read this in the late 90s.

LSP: Was it a book you just came across in a store? Or someone told you to read it?

CT: Oh, I know what happened here. I had a story in Terry McMillan's anthology Breaking Ice back in the 1990s. That anthology actually introduced me to a number of writers I hadn’t read before. One was Charles Johnson. Another was David Bradley. And there was an excerpt from this book in Breaking Ice. It's a wonderful book, because it's a really unsentimental view of race relations. But it ends on a note about the need for trust and reconciliation.

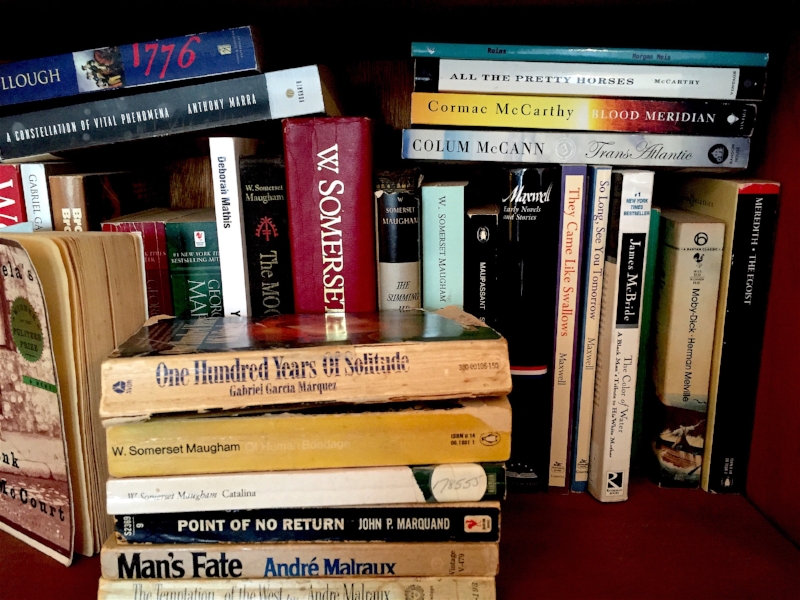

LSP: What about in terms of writing? Which books have you read either recently, or a long time ago, where you just thought: if I could one day articulate this feeling like this. Was there anyone specific?

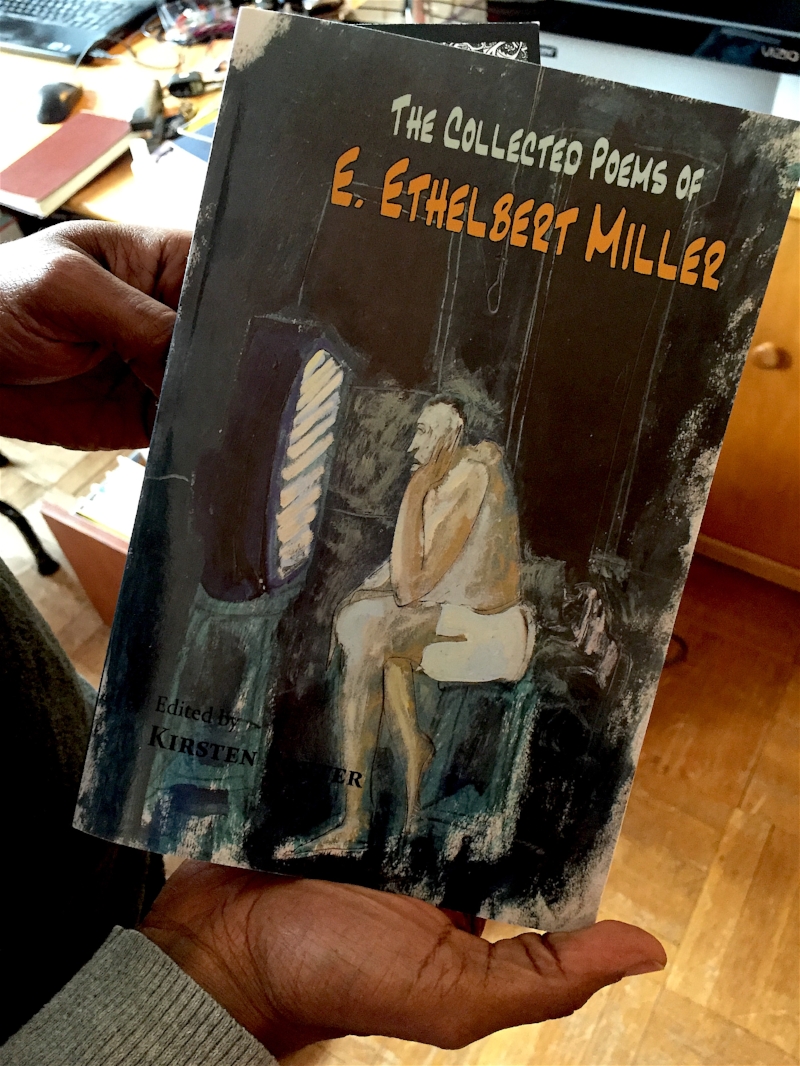

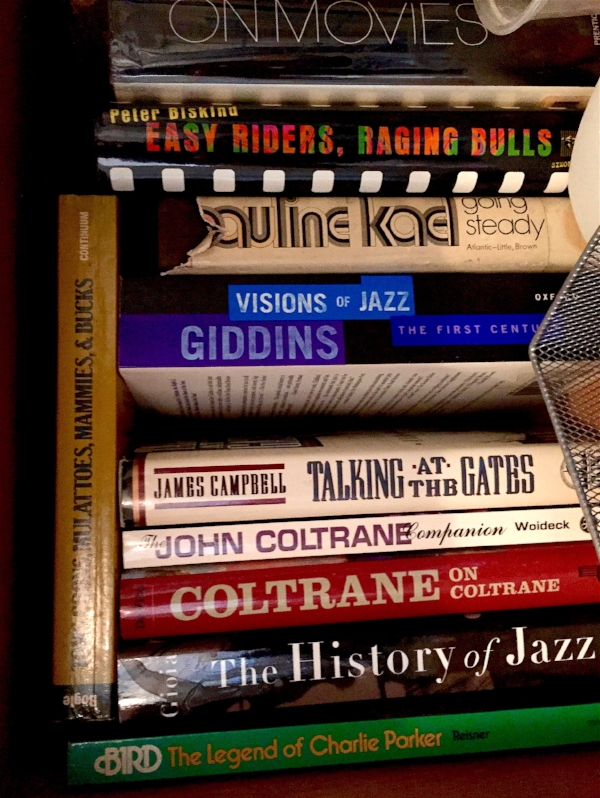

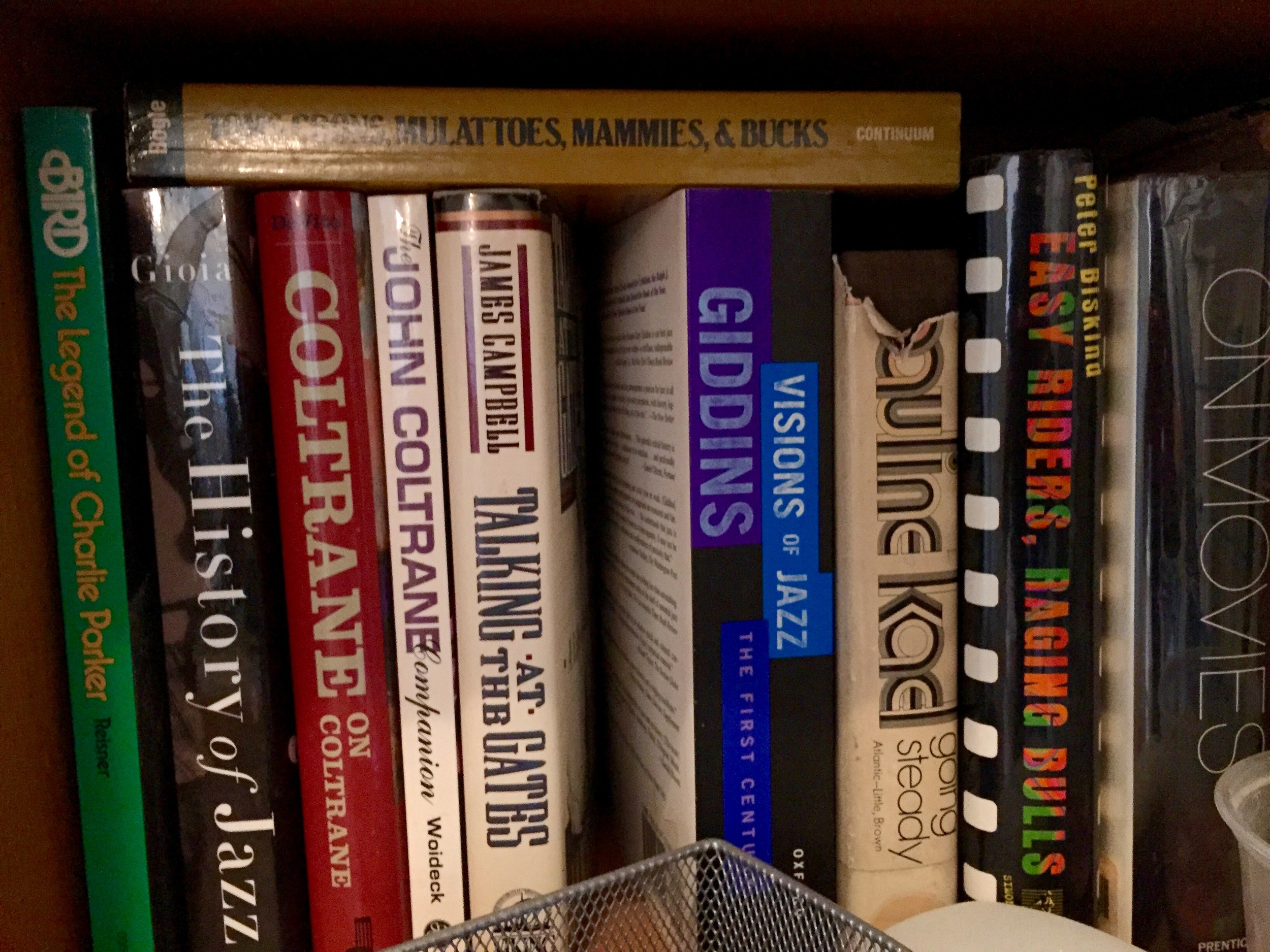

CT: These are Albert Murray's books. Here is one, The Hero and the Blues. I would say he, Murray, had possibly the most powerful effect, if not on my actual writing, then on my thinking as a black person and as an American, and about the inextricable relationship between blackness and Americanness, and about all Americans, and about the black American tradition.

LSP: It looks like – it could just be the front cover – they are comparing [what’s inside] it to a Charlie Parker solo. Obviously music’s in there, which is something that is so important to your self-identity and the way you write about the American experience.

CT: His aesthetic is very much rooted in jazz and blues. And I was already a jazz fan before I came to his writing, but that just spurred me more to investigate it.

LSP: On your shelves, what is the percentage of read and still-to-read?

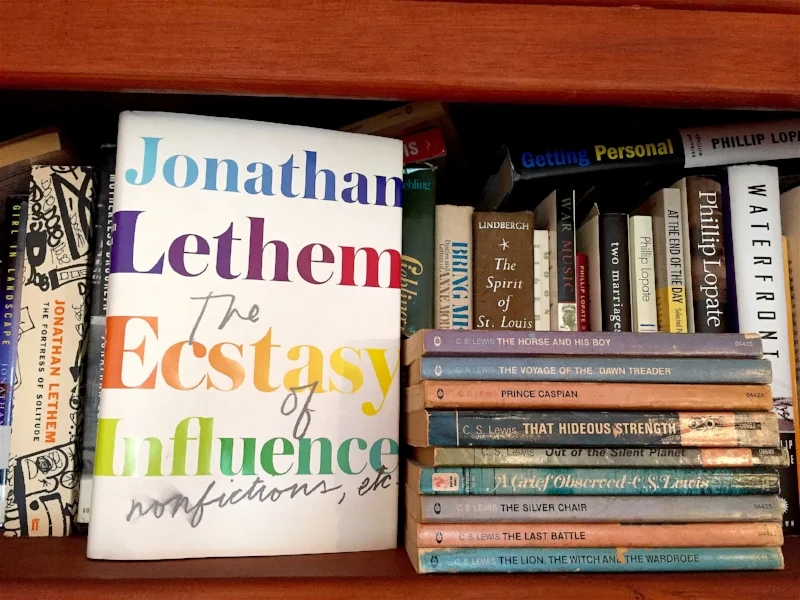

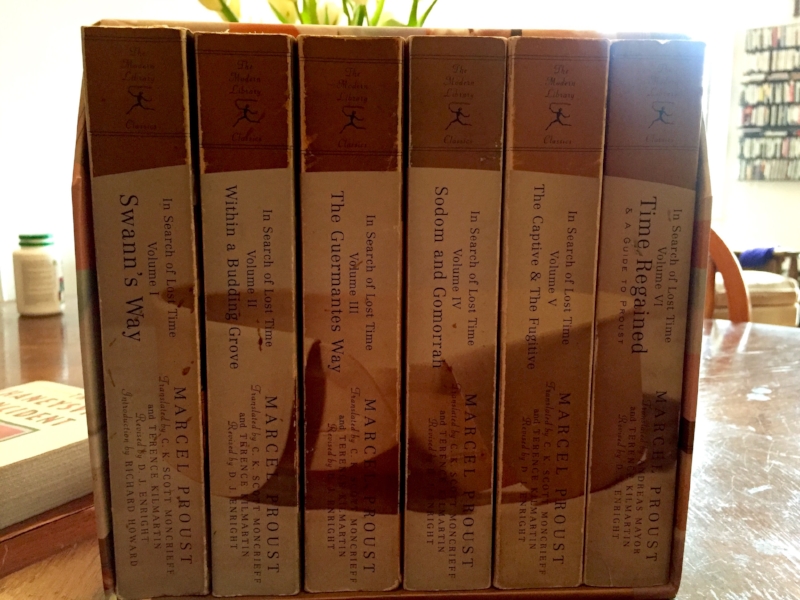

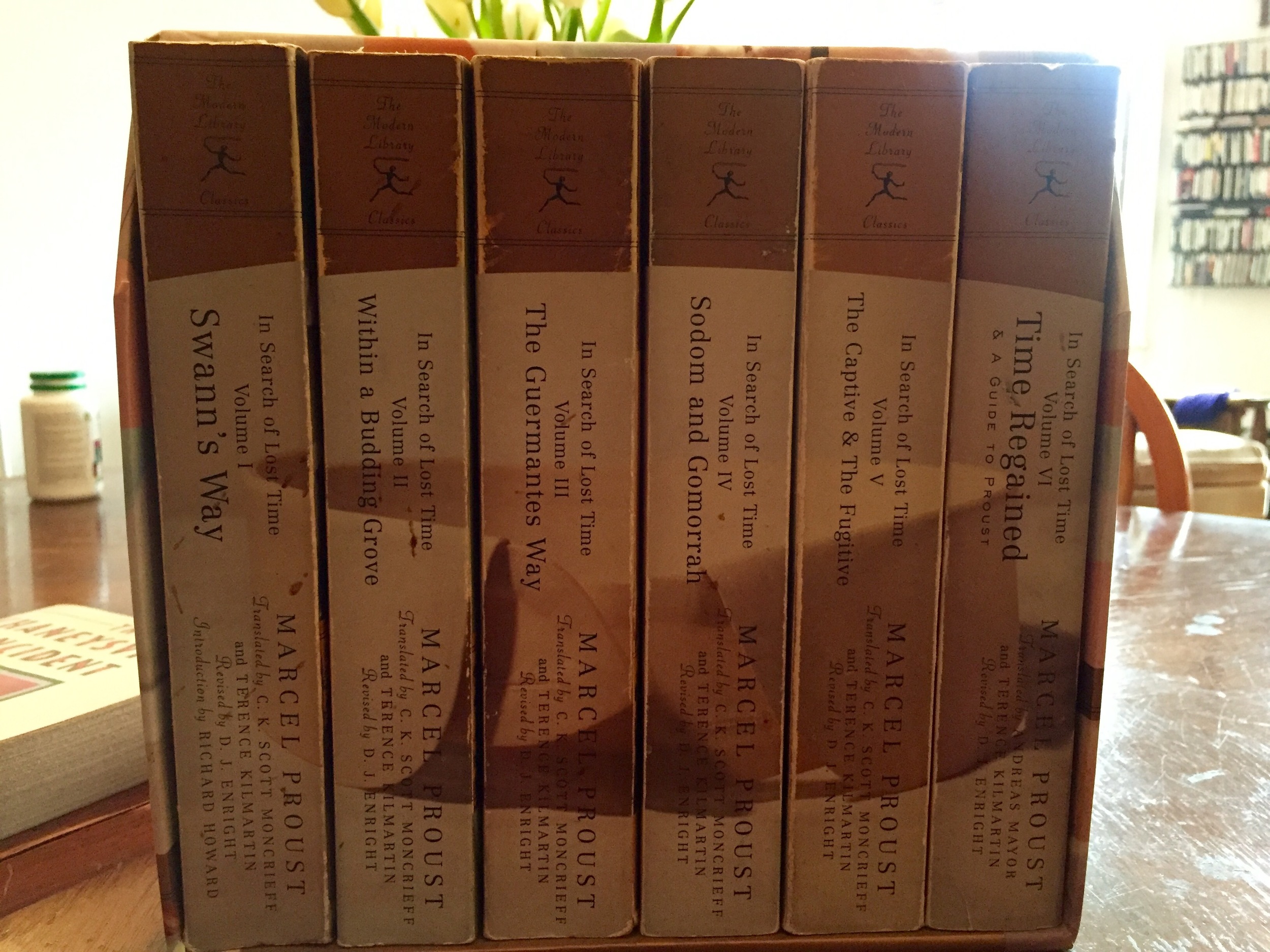

CT: Still-to-read is a significant percentage. Now this [Marcel Proust collection] really can't be topped by anything, foreign or American. This is the complete In Search of Lost Time, also known as Remembrance of Things Past. It’s just wonderful. I read this in 2004. I want to read it again sometime soon.

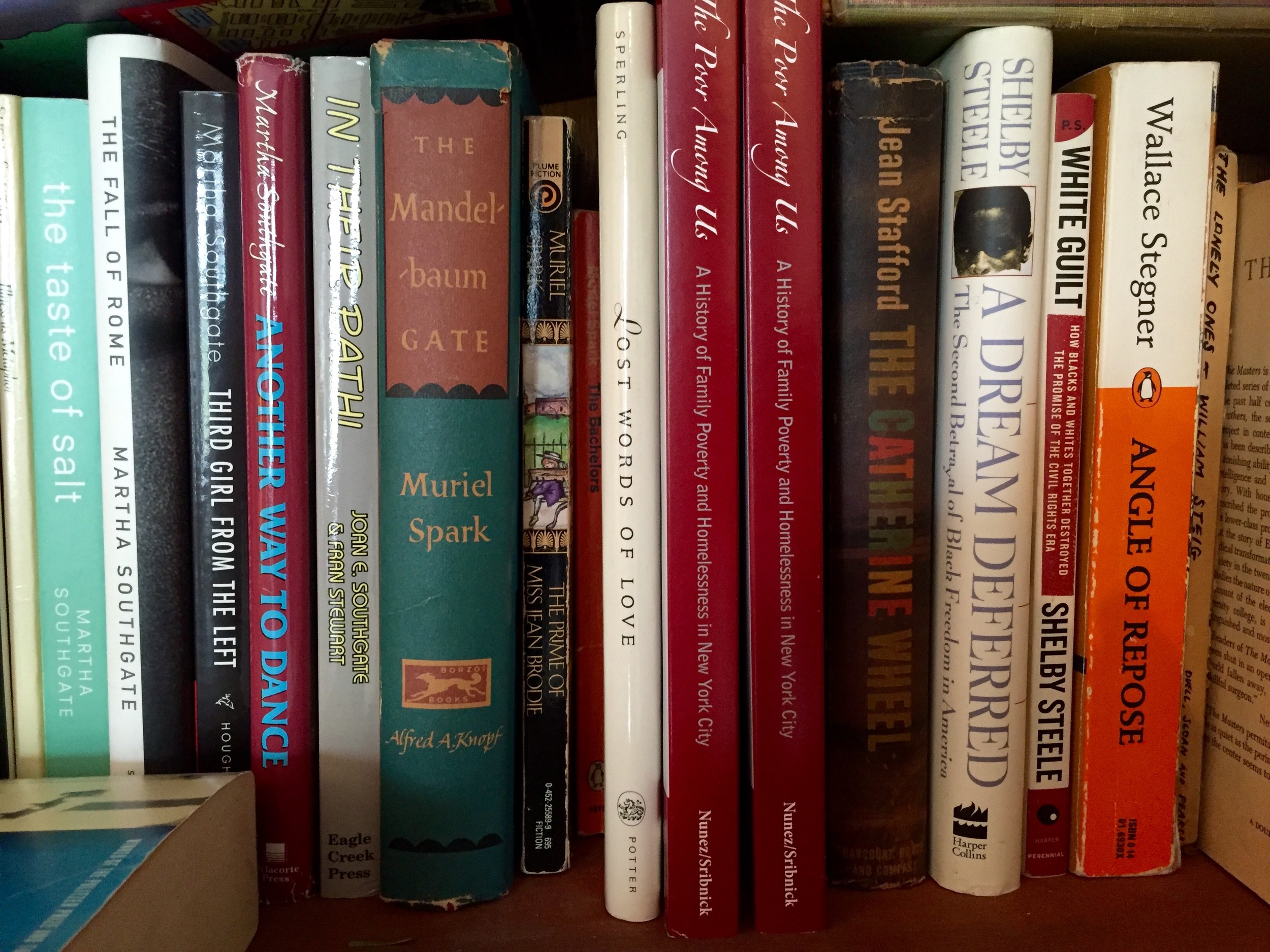

LSP: What about female writers?

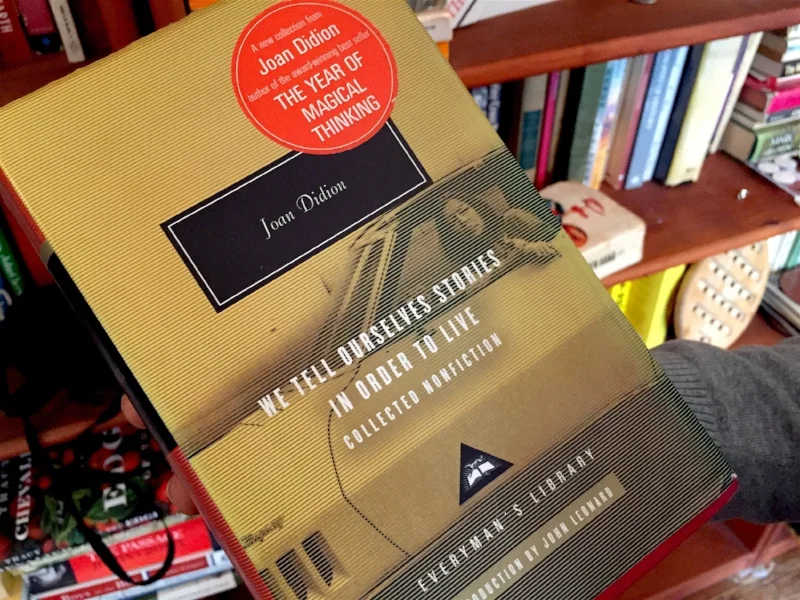

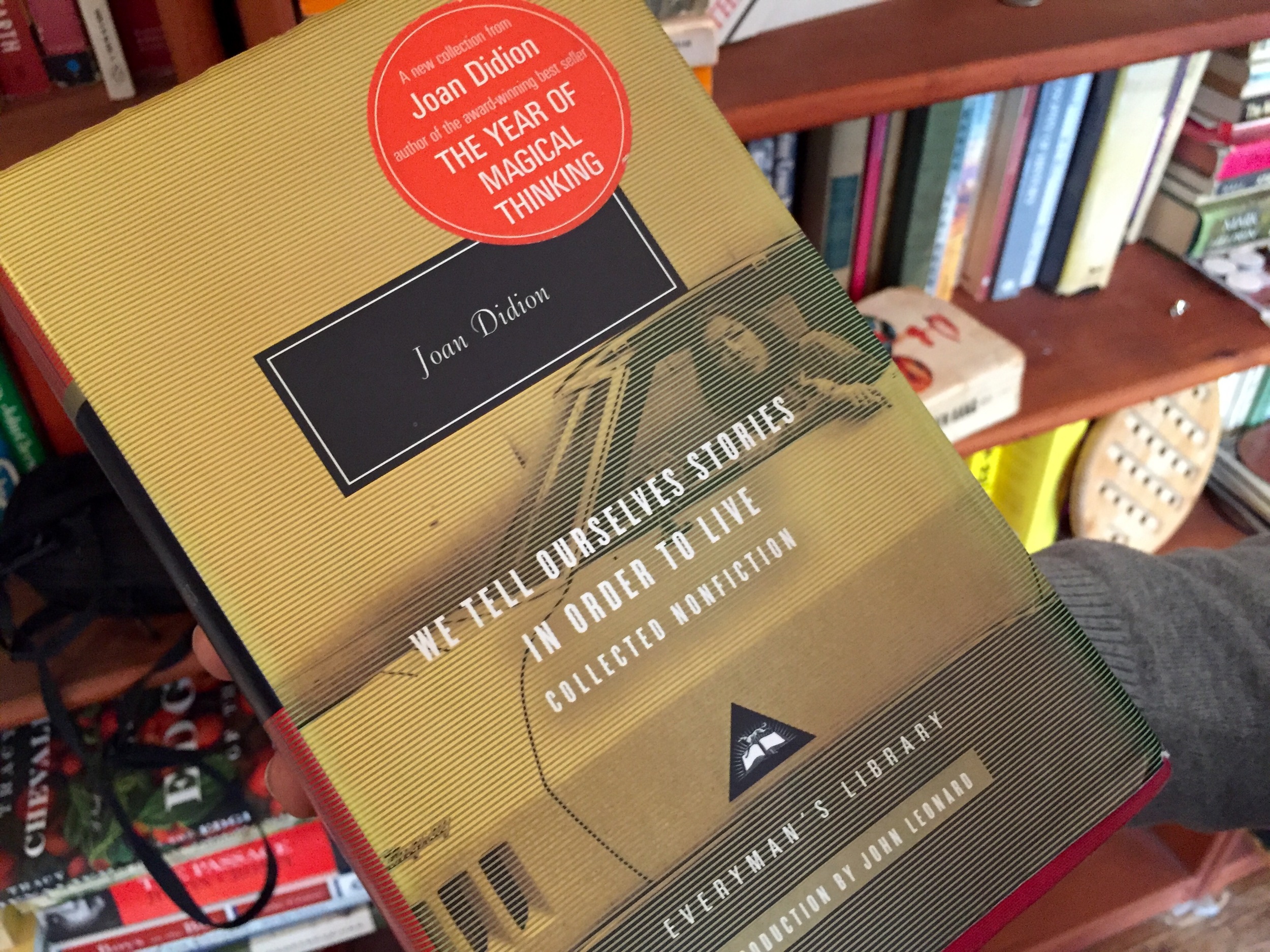

CT: For female writers, I’ve got to go with Joan Didion. This woman is fabulous. I just started rereading some of her early essays and I want to progress through the other essay collections and novels. She just has this way of seeing behind things. And just on a sentence level, she’s wonderful. She is a real hero for me.

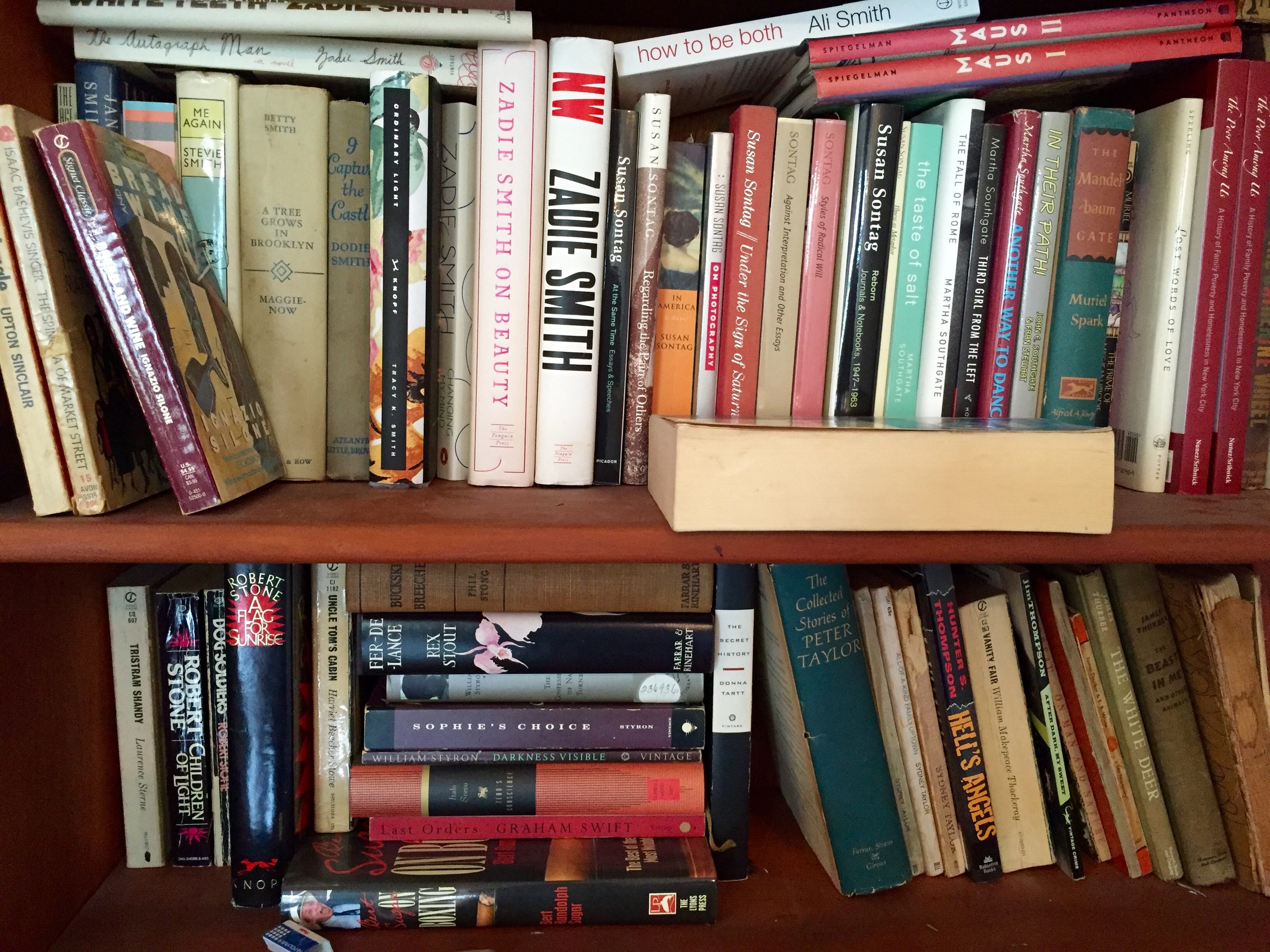

LSP: Which books have you read in the last year that you loved?

CT: I read Tracy K. Smith's memoir Ordinary Light. It was nice and leisurely. You kind of felt like you had spent some time in her house, where she grew up in California. There's a lot in there about her relationship with her mother, which is really intimately drawn. There's a nice interweaving of her relationship with her mother and the evolution of her feelings about religion, because the two are really intertwined.

I was just on a panel, and I tend to over-prepare for things, so I was asking people, I asked Margo Jefferson for suggestions of things I might not have read. She said there's James Weldon Johnson's autobiography Along this Way. The man did everything. He had insights into race and America that are still worth looking at today. He was such a crusader and a thoughtful individual.

LSP: What would be the breakdown of fiction versus non-fiction…

CT: That I read? For a long time ago, it was half and half. For 19 years, I worked in the Bronx, and I lived here. So I would take the train every day; I had an hour and a half time for reading. So I read novels and other fiction to and from work. And at home I would read essays and other non-fiction. So it broke down that way pretty evenly. These days, partly because I teach non-fiction, I read more creative non-fiction than fiction. But I still love to read fiction.

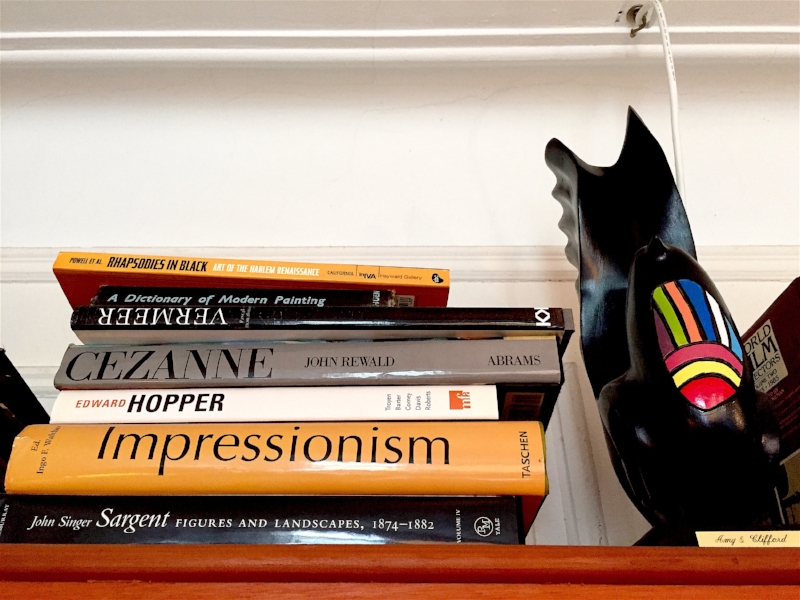

LSP: You’re an artist. And your art is both on the cover of the essays and also your memoir. Did you do those postcards over there?

CT: I did those.

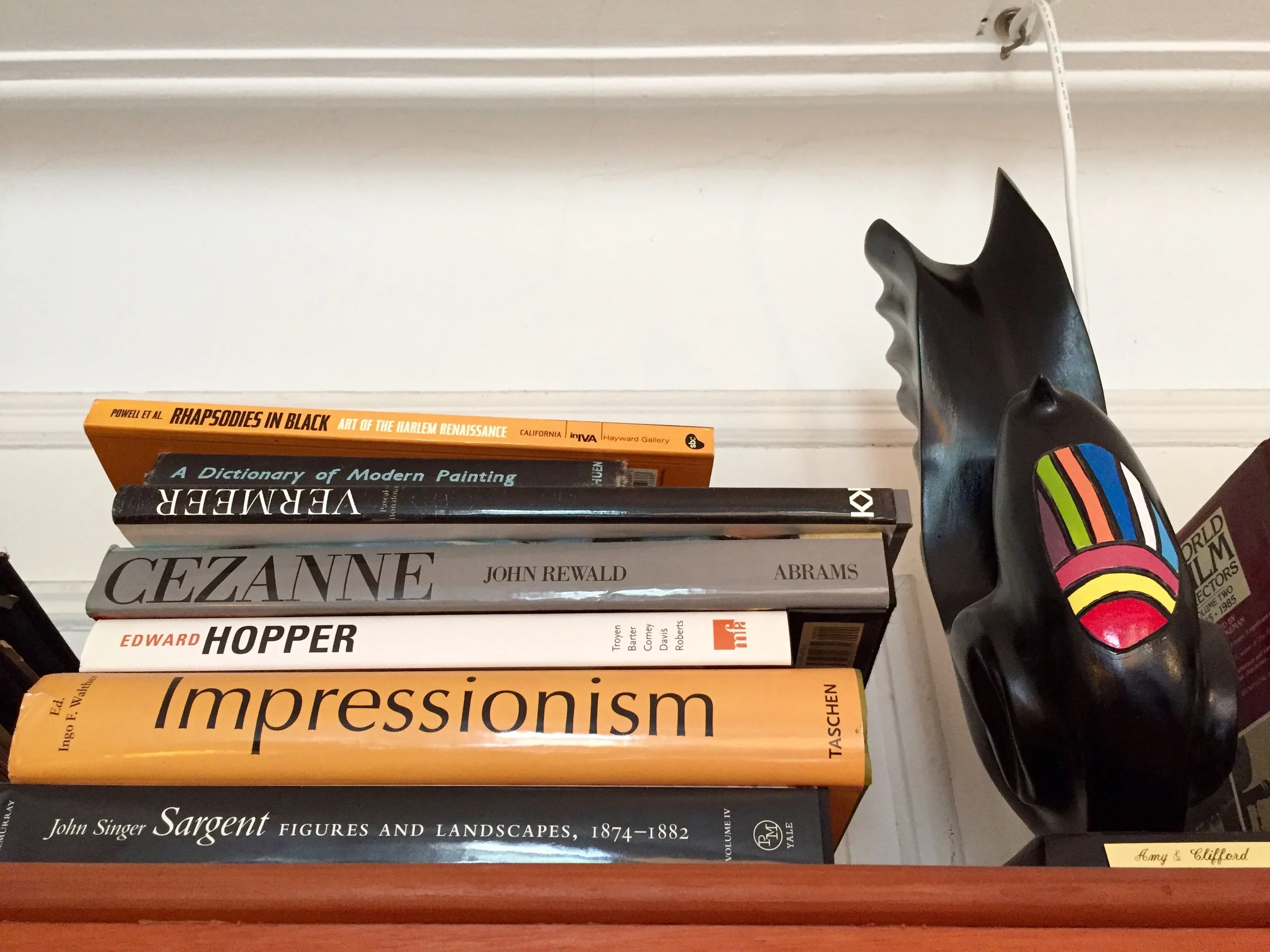

LSP: When did you start painting?

CT: I was in my mid-40s. And I suddenly got the bug. I drew comics as a kid. The comics were a mix of words and pictures of course. And for so long, the words left the pictures behind. But I felt an itch from time to time over the years. And then when I was about 45 and suddenly I just felt like painting. And I haven't stopped.

LSP: Where do you paint?

CT: Here’s an easel my wife got me years ago. So I open it up and put it here.

LSP: Are these paintings non-fiction or fiction?

CT: (Laughs) Good question. Some are one and some are the other, I suppose. I used to sell these out on 7th Avenue. I haven’t for a long time. I’d go down to 7th and President and sit on the street, people would come and by.

LSP: So this one, that was on the cover of…

CT: That was Love for Sale. When the book was going to be published, I said to the publisher – we were talking about the cover – and I said oh, I have these paintings, maybe one of these would make a good cover. So I sent this one and they said that's the one.

LSP: What are we listening to right now, by the way?

CT: This is a Miles Davis's record from the 50s, called Conception. He plays on it with Stan Getz and Lee Konig.

LSP: When you’re writing, are you listening to music? Or silence?

CT: It depends on the setting. I write a lot at the Starbucks these days. So there’s already music there.

LSP: Really? Because this seems like such a great place to write. Although, I guess it’s in your home.

CT: Yeah, exactly. Other people live here too and it’s not that big a place. So I need to kind of get away.

LSP: And the typewriter? Did you ever use that?

CT: I did, actually. I took that to a writing colony twice.

LSP: How was it to write on?

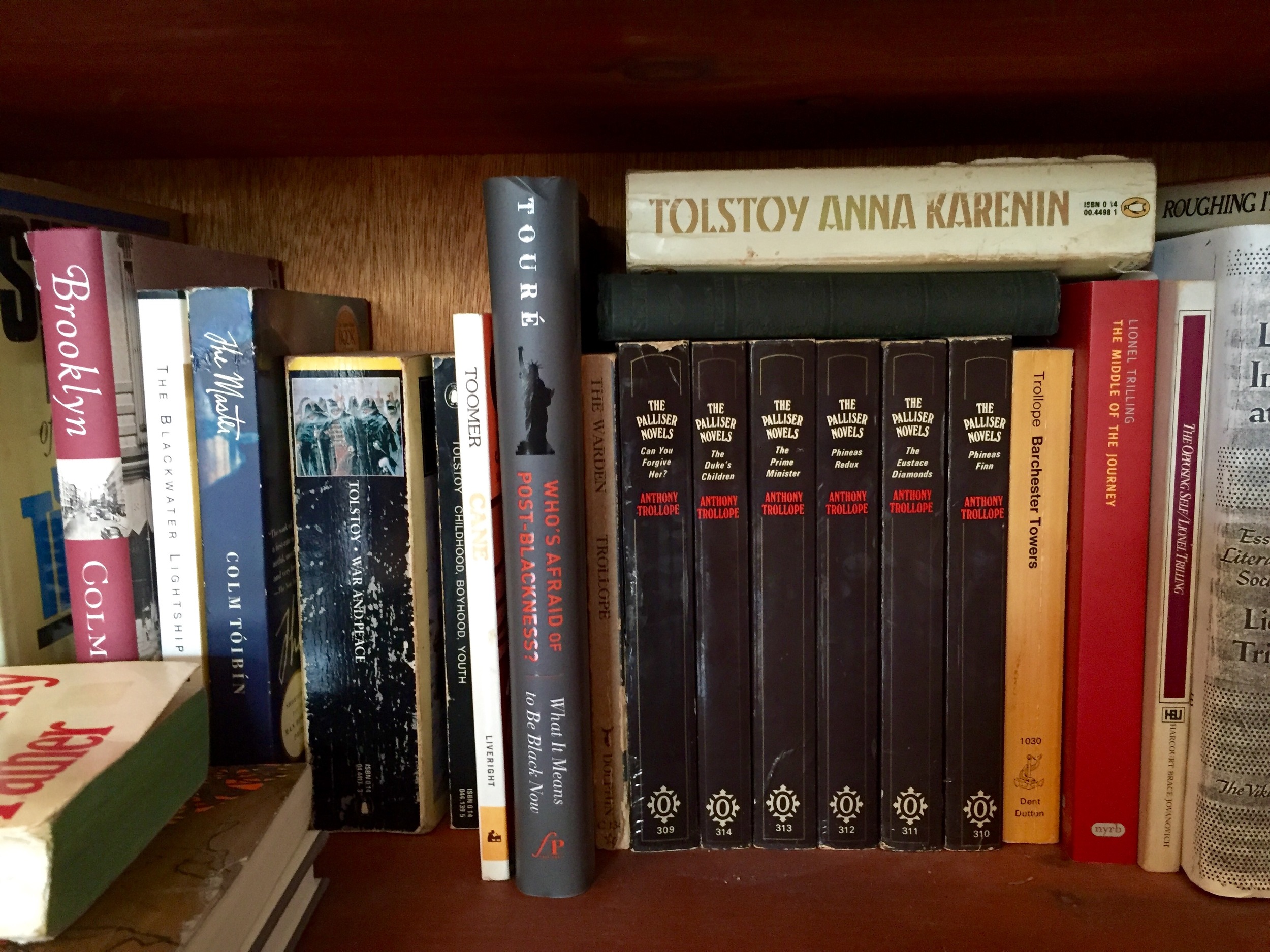

CT: Well, I don't know if I would do it now. Because I had to come back and copy everything I’d done. But I enjoyed it when I did it. These days it mostly sits there. Sometimes I write letters on it. I was recently in downtown Manhattan, I had a book with me for a class I was teaching. It was Phillip Lopate’s edited collection on The Art of Personal Essay. And I was reading his introduction to it. I got so inspired that when I came home, I thought: I got to write him a letter, email wouldn’t do it. And I had some homemade stationary so I popped it in and said, ‘Philip I was just reading this collection…’

LSP: Did he respond?

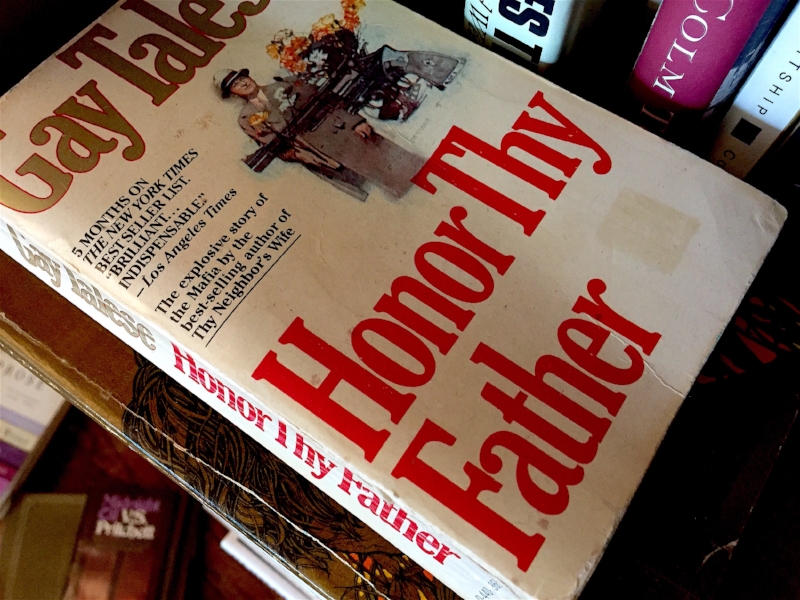

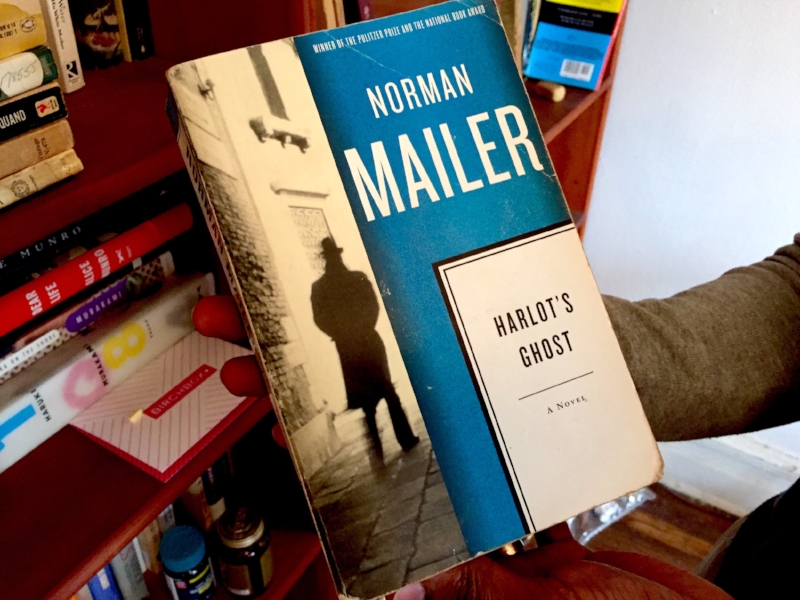

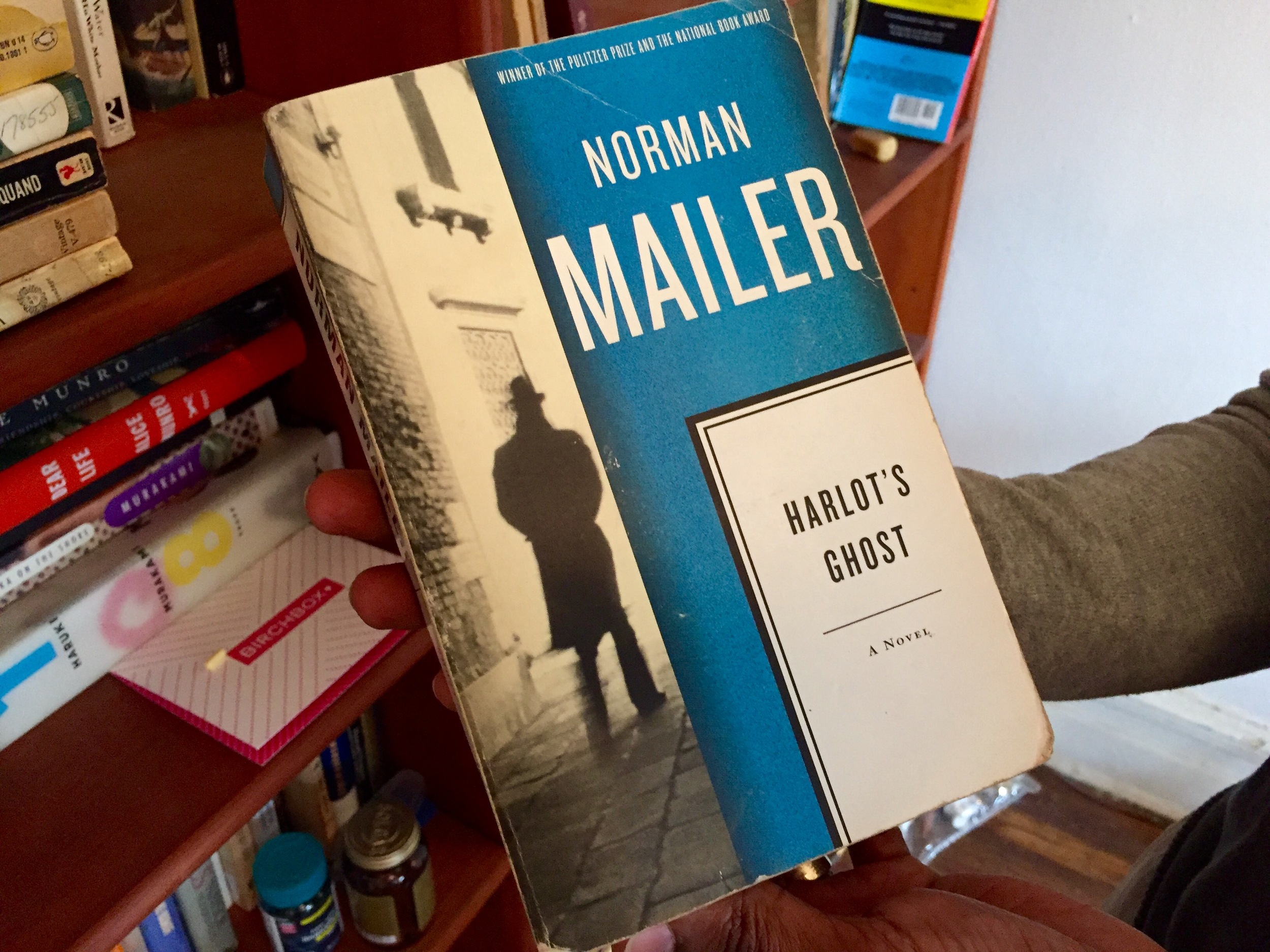

CT: Yes, I got an email from him later. He’s a friend. We peruse his shelf. This is Harlot's Ghost by Norman Mailer. It's an-1,100-some-odd pages and its plot doesn't resolve, because I think he was planning to write more. So it's very long and the story doesn't really come to an end. But it's one of the most amazing things I have ever read. It's a story about the CIA. It's fiction. It's fantastic. Nobody will read it cause it's so damn long. And it doesn't really end.

LSP: When you got to the end, though, were you deflated? Or was it worth it anyway?

CT: It was worth it. It was completely worth it. The perusing continues, he picks up a Susan Sontag book. Susan Sontag is wonderful. I teach creative non-fiction and there are some essays I keep coming back to. One is Jo An Beard's collection called The Boys of My Youth.

LSP: How do you go about teaching?

CT: A lot of the essays I teach are personal essays. So I spend a lot of time trying to analyze the ways writers do things and what makes the essays distinctive. I teach the essay Notes of the Native Son. One of the things I really respond to in that essay is just the music of a language, and also syntax – the arrangement of words in a particular sentence just can say so much about a person's sensibility. I give you one example. There is a line in the Notes of a Native Son, where he’s almost talking about his father, and the line is, "he was, I think, very beautiful." And just thinking about the arrangement of those words, and how they’re different from, "I think he was very beautiful" or, "He was very beautiful". That thoughtfulness and hesitation that he conveys with the arrangement of words and the arrangement of commas and what that signifies. Then you get to understand how important every word is and every element of construction of a sentence in conveying what you’re trying to say, and also in conveying a rhythm and a music.

LSP: Speaking of music, who’s this?

CT: This is Miles Davis, Porgy & Bess. He picks up a book by Hermann Broch. This is a great book. You were asking about foreign writers. This is a novel I really thought was powerful and it’s funny I picked these books up - The Sleepwalkers trilogy - because I know about this because of this. He picks up a book called Kafka Was the Rage.

LSP: You know The Sleepwalkers because of Kafka Was the Rage? Why, because it’s in there?

CT: He opened a bookshop in Greenwich Village in the 40s and he was talking about some of the books he stocked and this was one.

LSP: That’s great, you can get book recommendations from within the pages of other books…