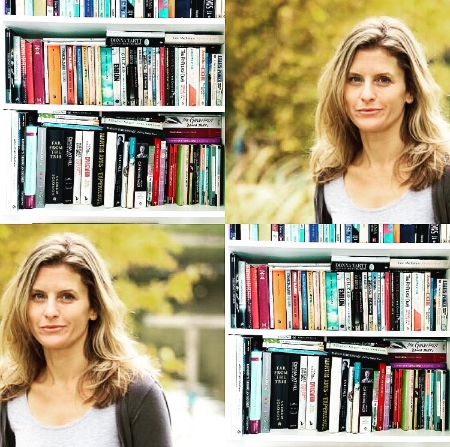

A BOOKSHELF ODYSSEY: ALICE ADAMS'

/By Katya Wachtel

We first met English author Alice Adams in real life, at a cocktail party in downtown Manhattan, where she had come to celebrate her forthcoming debut novel, Invincible Summer (Little Brown). We met her for the second time in space, on Skype, in mid-April.

Adams' bookshelves are located in "the snug" of her North London home, beside a large window. What is a "snug?" we query. "Oh, is that too English?" she replies, then sources a dictionary translation: "Snug 2 (snŭg). n. Chiefly British. A very small private room in a pub."

"Though obviously it’s not in a pub," she adds. "It’s a smallish room off the living room."

Adams grew up in England, then moved to Australia - where her mother is from and because she "fancied living in a hot climate" - before returning to London, where she has lived for more than a decade. She describes her relationship with the city as "love-hate."

Once a banking analyst, now a full-time writer, Adams is working on her second novel. Her first, out in June, follows the lives of four friends over several decades as they navigate adulthood from Bristol to Corfu to the villages of London and the English coast. Invincible Summer takes its name from a 1952 essay by Albert Camus called Retour a Tipasa - one of Adams' favorite essays.

"Au milieu de l'hiver, j'apprenais enfin qu'il y avait en moi un été invincible," Camus wrote, which translates to, "In the depths of winter, I finally learned that there lay within me an invincible summer." In his essay, Camus "returns to the Algiers of his childhood after the war," Adams explains. "Obviously a very dark period of human history, and wanders around the ruins reflecting on things like war, courage, beauty and justice."

"I have it framed on my wall."

* * *

The Literary Show Project: Have you lived in London all your life?

AA: No. I was born here but moved around the UK a bit during childhood and did a stint in Australia after university... I’ve been back in London for the last ten or fifteen years. I have a love-hate relationship with the place -- it’ll always be a piece of my heart, but increasingly I yearn for wilderness.

LSP: So, onto your bookshelves and your books. Is there any rhyme or reason to their organization? Or is it a more haphazard operation?

AA: It’s wholly haphazard. They are vaguely clustered by author but even that doesn’t really hold as a rule. Anally retentive though I am in many areas of my life and thinking, it does not extend to my bookshelves. Though I would add that I pretty much know the location of any one of the hundreds or thousands of books I own.

LSP: It sounds like you don’t often get rid of books. I’ve read that Junot Díaz keeps every book he has ever bought, but writers like Edmund White and Claire Messud prune their library from time to time.

AA: In my early twenties, as I left university and set off for Australia with no particular intention of coming back, I did a thing that I have regretted ever since: I sold all of my books to a book shop. There were thousands: my philosophy books, my maths books, a lifetime’s worth of fiction. I had a theory about being unencumbered, about there being a certain joy and simplicity in being able to fit everything one owned into a rucksack and set off on an adventure. Huge mistake. Huge.

So all of my books have been bought since then, and I rarely prune. Though I often lend books which are never returned. Annoyingly these are always my favorites. Books are the exception to the rule that material possessions are not worth hoarding.

"Anally retentive though I am in many areas of my life and thinking, it does not extend to my bookshelves."

LSP: So which books are so dear that you’d never lend them out? Do you have any like that?

AA: Hmm. No, I don’t think so. It’s actually probably the inverse - the dearer a book is to me, the more likely I am to end up pressing it into the hands of someone I think might need it.

LSP: So which of your favorites are currently out on loan?

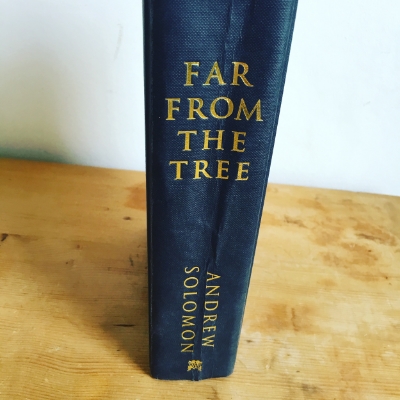

AA: That Far From the Tree is I think the third copy I have bought - its predecessors were lent out and not returned. It’s one of those books that can make a big difference to people in some of the most difficult areas of their lives, so I don’t resent spreading it far and wide.

LSP: How did you come across that book for the first time?

AA: I actually heard an extract on the radio, BBC Radio 4. I had it on in the car and it was an interview with the mother of one of the Columbine killers, the two teenage boys who carried out a school shooting in the US some years ago, killing many of their fellow students and then committing suicide. I ended up parking the car and just sitting there listening till the end of that interview - it was as fascinating and devastating as you might imagine.

So I bought the book, which broadly is about children who are different to their parents in some way: gay, prodigies, transsexual, autistic, disabled, Down syndrome, killers. It was one of the most impactful books I have ever read, and if I could choose a single book that I could force every single person on the planet to read for the good of mankind, this would be it.

LSP: It sounds like an incredible book. Do you read as much non-fiction as fiction?

AA: Increasingly I do. I used to be strictly fiction, but lately I find the balance shifting in favour of non-fiction and I’m probably now fifty-fifty.

LSP: So is there another non-fiction book on your shelf that has been a game changer for you? Or perhaps one that has impacted your own writing?

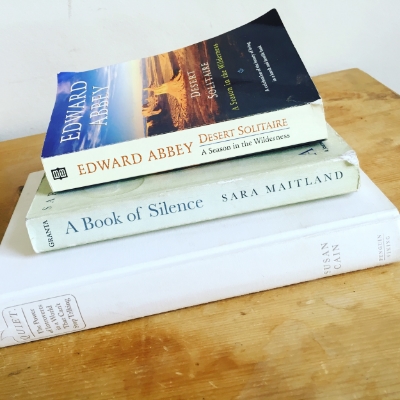

AA: Just occasionally a book makes a little change to the shape of your soul and for me, Sara Maitland’s A Book of Silence was one of those books. Her descriptions of moors and desertscapes, hallucinations and revelations captivated me and gave form to a hitherto unarticulated yearning for silence and solitude in my own life.

"I rarely prune."

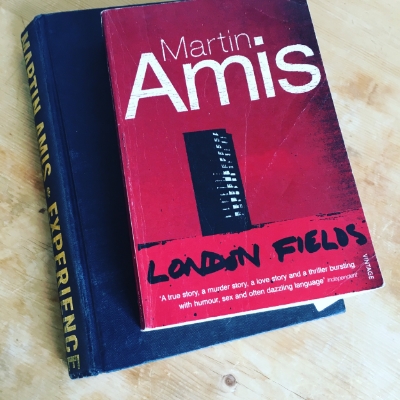

LSP: So which fiction has changed your soul? As a person, as a writer? I see a few Martin Amis books on your shelf.

AA: Yes. The first book I can remember reading and being so dazzled by what it did that it made me wonder whether I could or should try to do it myself was London Fields, which I read in my teens. Amis at his best blows everyone else out of the water. For sheer linguistic genius, but also for his humanity, his tender understanding of the joy and tragedies of life. I think for many people that would be a controversial statement, but that is my view.

His autobiography Experience is also truly wonderful, perhaps the best I’ve read. Of course there are books of his that I love less but I don’t think there’s any reason to be snarky about that - to create great work you have to take risks, and sometimes they pay off and sometimes they don’t.

LSP: You took a course with Amis I believe?

AA: Yes. He was a lecturer on my MA course. Of course, everyone on that course dreamt of being his protégée but what it really amounted to was going along to his lectures on the Russians, Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky and Nabokov and so on, and dragging him to the pub once or twice where we made him visibly uncomfortable by sitting staring at him in silent, trembling reverence. I did bum a cigarette off him once or twice, too.

LSP: And you have some T.S Eliot – are you a big poetry reader?

AA: I’m not a particularly systematic reader of poetry and have never studied it. But I do read poetry and some of it is very close to my heart - TS Eliot’s Four Quartets, which contains much of the wisdom you need for a life and which I come back to over and over again, but also stuff like Michael Donaghy, Clementine von Radics, Don Paterson.

LSP: Do you read poetry then more for pleasure? Ie. do those writers affect your own prose, or would you say its novels that have been more influential on your own work?

AA: I both read and write poetry for pleasure. I haven’t given any thought to whether that has any bearing on my fiction writing. It feels like a very different discipline, but I suppose it’s good practice to have to pay close attention to every sound and nuance, rhythm and scansion. But novels have been more influential on my novel writing.

LSP: So apart from Amis, which other books on your shelf are particularly meaningful, in the fiction category?

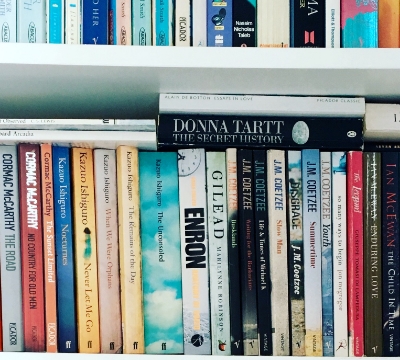

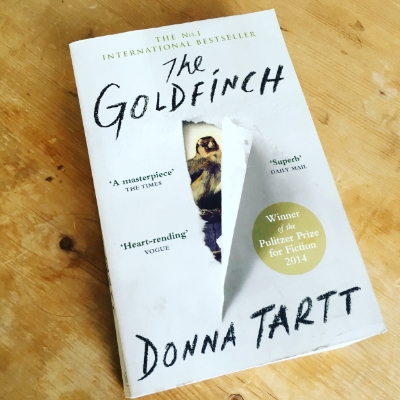

AA: My recent favorite is Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch. All writers have those books that you finish breathless, wracked with despair that you will never write anything so good, and The Goldfinch was one of those for me.

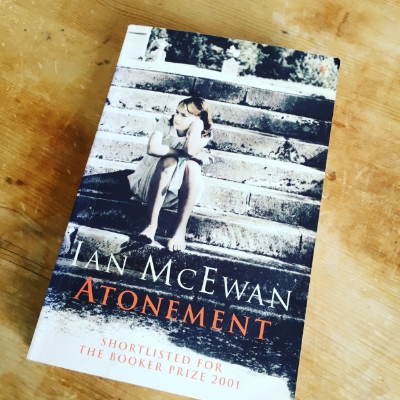

LSP: I always ask about The Secret History - Donna Tartt's first book - when someone mentions The Goldfinch because its one of my all-time favorites and I much preferred it to The Goldfinch. I see you have The Secret History on your shelf. Have you read that yet? If so, I assume from your mentioning it you preferred The Goldfinch?

AA: Yes. But not for many years so it would be hard for me to compare the two. I think, though, that it would be The Goldfinch for me. This bears out an observation I have made previously, which is that The Goldfinch has been an unusually polarising book.

LSP: I love a university tale - as The Secret History was - and as your own book begins.

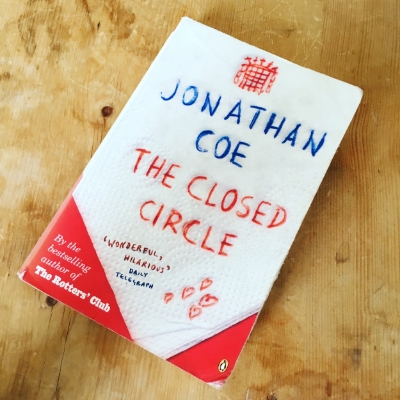

"The Closed Circle is... Jonathan Coe at his luminescent best... if I ever write anything half this good it will all have been worthwhile."

AA: Well, do check out The Rotters’ Club and The Closed Circle (sequel), which are ‘coming of age’ type novels. Though they are deeply English, and may not be enjoyed so much by other audiences, hard to say. The Closed Circle is a book that has withstood repeated readings over the years and is Jonathan Coe at his luminescent best. It's honest, beautifully written, funny, political and redemptive, and if I ever write anything half this good it will all have been worthwhile.

LSP: Now, in a former life you were a banking analyst.

AA: Yes. A number cruncher. I spent ten years working in banking, doing analysis on various different types of data and information.

LSP: Are there books on your shelf that hark from these days, like that Michael Sandel one, What Money Can’t Buy?

AA: Hmm. I think that was a later read for me, but it’s certainly fed into my thinking on economics and politics. This book is an invaluable contribution to any debate on capitalism, and makes a strong case that many, if not all, economic questions are also matters of morality.

During my time in banking I gradually gained an understanding of the ways in which markets fail, as well as what is often a lack of better alternatives. Some of those dilemmas and observations are woven into my novel Invincible Summer, and this book was a valuable part of the evolution of my thinking on these matters.

LSP: Did you always plan on weaving this personal history into a novel, or into a character?

AA: No. And I would like to stress that the novel is fiction and not autobiographical! Naturally it contains settings and milieus with which I’m familiar from my own life, because that makes it possible to write with verisimilitude, but it’s in no way autobiographical and I identify as much with Benedict, Sylvie or Lucien as I do with Eva. Plus, I don’t actually plan my writing, it just sort of plops out onto the page. This is another deviation from my usual personality, which is pretty well organized and systematic, but it’s just the way it has turned out to work for me with writing.

LSP: What are you reading right now?

AA: River of Time, a memoir of the Khmer Rouge years in Cambodia by journalist Jon Swain, on whom the journalist in the film The Killing Fields was based. It’s not for the faint hearted but was recommended by a friend whose judgement I respect.

LSP: And finally, who is that cat in your Skype profile picture?

AA: Ah, that’s just a random cat picture I culled from the internet. I don’t have a cat at the moment but have had many rescue cats in the past and adore their whiskery mysteriousness. I secretly believe that I will end up one of those cat ladies, and am rather looking forward to it.

* * *

INVINCIBLE SUMMER IS ON SALE JUNE 28, 2016